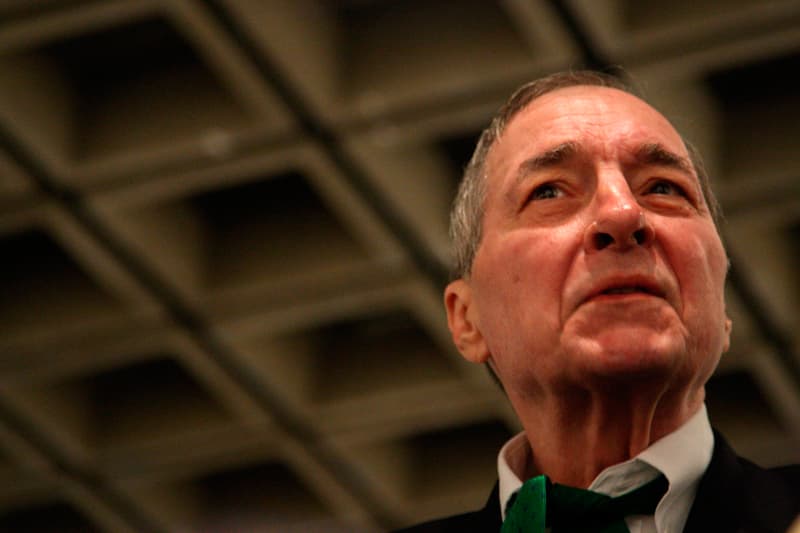

Image: William Eggleston at the opening of his William Eggleston Retrospective at Whitney Museum of Art in New York City on 5 November 2008. © Getty

When William Eggleston’s photographs were first exhibited in a one-man show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1976, the critics were almost universally hostile. They disliked his use of colour, which was at the time mainly used in commercial photography.

They derided his informal ‘snapshot’ style and his apparently inconsequential subject matter. In his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, John Szarkowski, the MoMA curator of photography and an enthusiastic champion of Eggleston’s work, had described his pictures as ‘perfect’. ‘Perfect?’ questioned The New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer. ‘Perfectly banal, perhaps. Perfectly boring, certainly.’

In the years that followed, however, perceptions of Eggleston shifted dramatically. For the vast majority of commentators, Eggleston became regarded as a pioneer, the father of colour photography as an art form. Major photographers and filmmakers cited him as an important influence on their work and even The New York Times (in 2008) was moved to describe him as ‘one of our finest living photographers’.

Eggleston, born in 1939 into a wealthy family that lived on a former cotton plantation in Memphis, Tennessee, first became interested in photography in his late teens. He shot in black & white, initially on a Canon rangefinder and from 1959 on a Leica, with his major influences coming from Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans. Even in these formative years, he concentrated on everyday subjects in suburban Memphis: people caught off-guard, supermarkets, diners, roadsides, fences and trees.

In 1965, he made the decisive change to working in colour and two years later travelled to New York where he met fellow photographers Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus, who suggested he should show his work to John Szarkowski at MoMA. Szarkowski saw the potential in the suitcase full of images presented by Eggleston and encouraged MoMA to buy one of Eggleston’s prints. Nine years later, Szarkowski organised the one-man exhibition that caused such controversy.

In the intervening years, Eggleston had begun using a process that was to give his work its unique quality. In 1972, he had noticed that a Chicago photo lab was advertising dye-transfer prints as ‘the ultimate print’. When he saw some examples of these prints, he was overwhelmed by the colour saturation and the quality of the ink.

‘Every photograph I subsequently printed with the process seemed fantastic and each one seemed better than the previous one,’ Eggleston tells Mark Holborn in the book Ancient and Modern (1992). ‘By the time you get into all those dyes, it doesn’t look at all like the scene, which in some cases is what you want.’ These prints provided the additional distance from reality that made his images so distinctive and helped Eggleston turn the everyday into the extraordinary.

Image: The tricycle photograph that appeared on the cover of William Eggleston’s Guide. Untitled (Memphis), 1970. © Eggleston Artistic Trust Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York

Image: The tricycle photograph that appeared on the cover of William Eggleston’s Guide. Untitled (Memphis), 1970. © Eggleston Artistic Trust Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York

The 1976 MoMA exhibition and the accompanying book William Eggleston’s Guide established his reputation and trademark style. On the cover was an image of a rusty, worn child’s tricycle, photographed almost from ground level so that it takes on a grand, monolithic quality. The image invites us to study the tricycle in detail and look at it afresh. It has become one of his most famous photographs.

In the 35 years since, he has photographed extensively around the world. He has produced numerous book projects, each one showing a small selection of images from the large numbers he shoots. These include Election Eve (1976), The Democratic Forest (1989) and Faulkner’s Mississippi (1990). He has also been commissioned to produce work on specific locations, usually either by museums or major companies such as Paramount Pictures and Coca-Cola.

Eggleston’s working methods have barely altered over the years. He says that he simply photographs things he sees around him, as, to him, ‘nothing is more or less important’. He works with anything from a Leica to a medium-format Mamiya Press camera and often photographs without looking through the viewfinder (in Mark Holborn’s words, ‘as if he was firing a shotgun’).

Another unusual aspect of his working method is that he never takes more than one photograph of a particular subject. He frames his picture quickly and instinctively, presses the shutter and moves on to the next subject.

At 71, Eggleston remains a unique, eccentric and enigmatic figure in contemporary photography. Interviewers invariably describe him as a ‘Southern dandy’, immaculately dressed in a dark suit, while mentioning his reputation as a ‘hell raiser’ with a fondness for bourbon, expensive cars and antique guns. Eggleston rarely discusses the motivation or meaning behind his work, beyond stating that he is ‘at war with the obvious’. He prefers his photographs to speak for themselves.

Image: Untitled (Sumner, Mississippi, Cassidy Bayou in background) 1971. © Eggleston Artistic Trust Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York

Image: Untitled (Sumner, Mississippi, Cassidy Bayou in background) 1971. © Eggleston Artistic Trust Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York

In an interview with Sean O’Hagen for The Guardian in 2004, Eggleston gave his reasons for not talking about his photographs.

‘A picture is what it is,’ he said, ‘and I’ve never noticed that it helps to talk about them, or answer specific questions about them, much less volunteer information in words. It wouldn’t make any sense to explain them. Kind of diminishes them.

‘People always want to know when something was taken, where it was taken, and, God knows, why it was taken. It gets really ridiculous. I mean, they’re right there, whatever they are.’

Biography

- 1939: Born in Memphis, Tennessee, on 27 July

- 1950s: Attends Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Delta State College, Cleveland and the University of Mississippi

- 1957: Begins photographing with a Canon rangefinder and is given a Leica the following year

- 1965: Starts working with colour negative film. He moves on to transparency two years later

- 1967: Meets Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus, and presents his work to John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art in New York

- 1972: Eggleston’s first dye-transfer photograph printed

- 1974: Appointed Lecturer in Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University. Awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship

- 1976: First one-man exhibition of colour photographs displayed at the Museum of Modern Art

- 1978: Appointed Researcher in Colour Video at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- 1996: Receives a Distinguished Achievement Award from the University of Memphis

- 2004: Presented with the Getty Images Lifetime Achievement Award at the International Center of Photography

- 2005: The documentary William Eggleston in the Real World, by Michael Almereyda, is completed

- 2011: A $15million project to build a museum to house Eggleston’s work in Memphis is launched

Books and websites

Books: A number of William Eggleston’s books are currently in print. They include William Eggleston’s Guide (1976), Two and One Quarter (1999), William Eggleston: Paris (2009) and William Eggleston: Before Color (2010).

Websites: Eggleston’s official website is www.egglestontrust.com. It features portfolios, a wide range of articles and essays, and biographical material. Several short films of Eggleston at work and being interviewed can be seen on www.youtube.com.