Working through 35,000 scans of Apollo moon landing mission imagery and ‘remastering’ the best is a massive job, but Andy Saunders did it magnificently, as Geoff Harris discovers.

When one considers the greatest achievement of the 20th century, the Apollo missions to the moon must be very strong contenders – unless you’re one of those unhinged conspiracy theorists who believes it was all faked, but AP readers are much saner than that.

If the Apollo programme from 1968 to 1972 wasn’t impressive enough, a vast body of still and video imagery was also taken by the astronauts up in space or on the lunar surface.

You’d think they would have enough to worry about, especially the crew of the troubled Apollo 13 mission, but some 35,000 images were taken on state-of-the-art cameras (for the time), and subsequently stored in a frozen NASA vault in Houston. For half a century, almost every publicly available image of the moon landings was produced from lower-quality copies of these originals.

Apollo 11, 21st July, 1969 Hasselblad 70mm, 80mm lens f/2.8 by Buzz Aldrin NASA ID: AS11-37-5528. Buzz Aldrin’s portrait of Neil Armstrong, moments after their historic moonwalk. Dry air, pressure changes, moon-dust irritation and sheer exhaustion are thought to have contributed to Armstrong’s red, teary eyes. © NASA / JSC / ASU / Andy Saunders

Now, however, expert image restorer Andy Saunders has painstakingly worked on digital scans of this massive archive, bringing the original images to life as never before. His new book, Apollo Remastered, includes much more detailed shots of Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong from the first moon landing, Apollo 11, Jim Lovell and the Apollo 13 crew struggling to get their stricken transit craft back in one piece, and much more.

We caught up with Andy to find out more about this labour of love.

The right stuff

Andy begins by stressing that this project was never driven or funded by NASA. ‘NASA has an open-source policy, so anyone can access the image scans. They are more than happy for people to work on them.

I sent back the remastered versions of the scans to NASA, but it wasn’t like I was contacted by them at the beginning. Nobody else was working up the images, including NASA. We had the holy grail of the super-high-resolution Apollo mission scans and they were just sitting there on a server!’

Andy began by working on some 16mm footage of Neil Armstrong in order to pull out individual stills, before deciding to check out the whole Apollo back-catalogue. ‘There were 35,000 images, so I went through them all and digitally remastered the best. Each scan is 1.3GB, so even downloading them was an effort. I just decided to go ahead and do it – somebody needed to take the bull by the horns.’

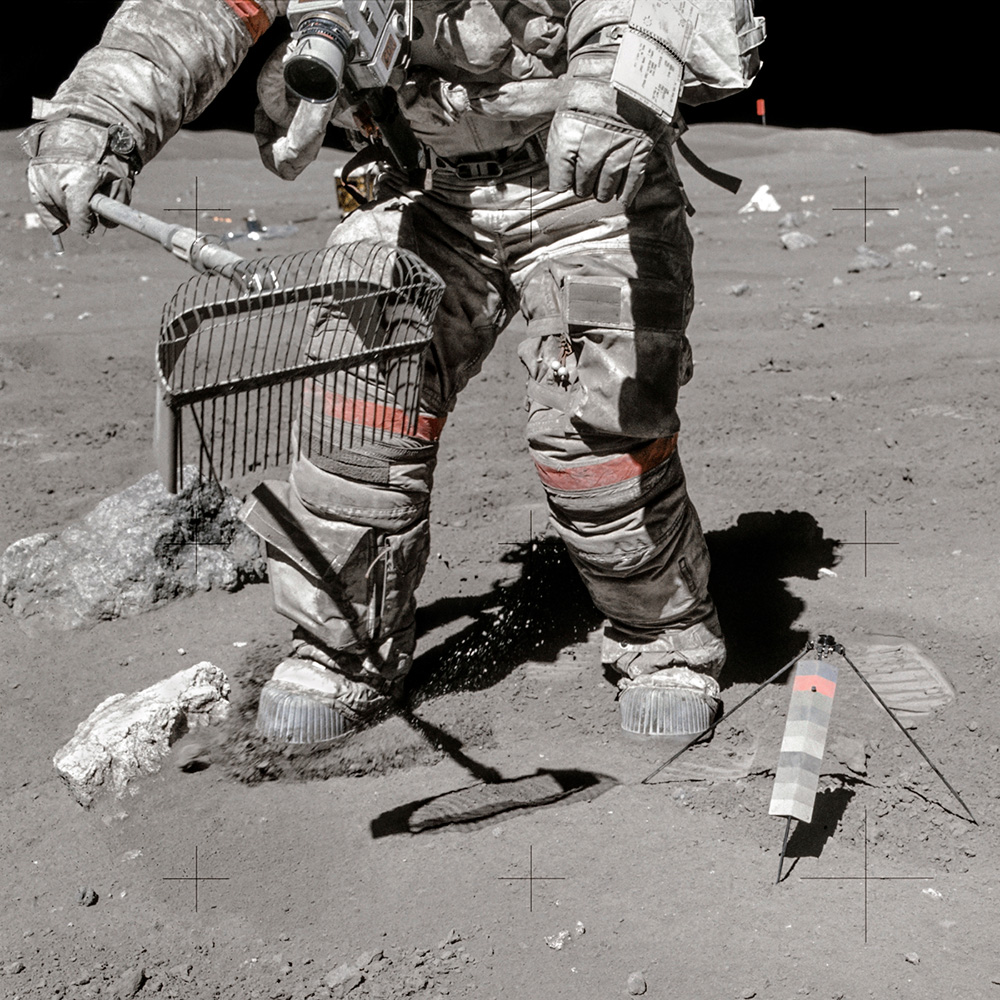

Apollo 16 mission commander John Young collecting moon dust. This remastered scan reveals a huge level of detail including the time on his watch! © NASA / JSC / ASU / Andy Saunders

An obvious question is why nobody had worked on the scans before in such a consistent and disciplined way. ‘If you think back over the last 50 years, for the first 25 we were still in an analogue world, without digital processing,’ muses Andy. ‘For the next 10-15, we moved into the digital imaging age, but the scanning technology wasn’t up the job.

‘Recently, however, there has been a step change in our ability to lift the data from this very delicate film, so NASA was keen to take the opportunity.’ Andy is affable and modest, with a dry sense of northern humour, but clearly had the ‘right stuff’ for this project, to name-check Tom Wolfe’s tribute to the first astronauts.

‘I could have gone into it half-heartedly, picking and choosing particular things to work on, but I really went for it. However time- consuming it was, I decided to try and get every ounce of goodness from the scans, or not bother at all.

‘I didn’t really know what to do with my enhanced images. I was sharing them on social media and when I started to see the great public response, I was motivated even more.

Apollo 11, July 20, 1969, 6 Frames Of 16mm Film, Stacked And Processed, NASA ID: APOLLO 11 MAG 1082-K. Armstrong progressed with collecting the contingency soil sample in case an emergency required an early abort. He’s preparing it in order to fit it into his thigh pocket. Regarded as the clearest image of Armstrong on the Moon, this shows for the first time, fine details and the recognizable features of the first man on the Moon. © NASA / Andy Saunders (Digital Source: Stephen Slater)

People particularly loved the Apollo 11 images of Neil Armstrong, and they started to get published in print and online. Then people started to suggest a book, and I could see the huge potential. Even when posting on social media, I was adding captions and context after going through the mission transcripts. By doing a book I could get everything in chronological order and add quotes from the astronauts too.’

Getting started

Andy’s interest in the moon landings goes back to childhood. ‘I loved rockets as a boy and the idea of taking one to the moon blew my mind. I wanted to learn more about the astronauts, who they were, what they did, what they wore… As I got older I appreciated more and more what an incredible achievement it was to get these rudimentary craft to the moon, in an age where computers were nowhere near as powerful as they are now.

I also loved the romance of the old film imagery – I’ve been into photography a long time, too, mainly working on event and architectural shoots but also following my passion for landscapes. I was somewhere between a serious amateur and a semi-professional photographer, so I did understand photo editing.

‘What really got me going was the movie footage of Neil Armstrong, where I started to develop my stacking process. I applied stacking to multiple frames of the 16mm footage of Armstrong, carefully reducing the noise, and was able to reveal lots of the detail in the subsequent still images.

Apollo 16, 23rd April, 1972EVA-3, Hasselblad 70mm. Lens 60mm F/5.6. By Charlie Duke, NASA ID: AS16-117-18826. Young, covered in Moon dust, is about to use the rake to collect a sample. From all the Apollo flight film, this photograph shows some of the finest suit detail. Young’s Speedmaster watch, set to Houston time, clearly shows 1:21 and 31 seconds, which ties well to the mission transcript time. The ALSEP can be seen behind. © NASA / JSC / ASU / Andy Saunders

It was reasonably straightforward to separate out the individual frames from the footage, shot on a Maurer 16mm Data Acquisition Camera (DAC). For the images of Armstrong, the camera was locked on a tripod, but most of the images I used in the book were from later mission footage shot handheld.’

Data monster

As Andy explains, ‘handheld’ in this context meant an astronomical challenge. ‘The handheld footage was taken by an astronaut, floating around in zero G forces, of another astronaut, also floating around. Trying to align and stack images taken in this “jerky” way on 16mm film was impossible, so I had to develop my own technique in order to obtain relatively high-quality still images.’

He is justifiably proud of the end result. ‘The images in Apollo Remastered take you inside the spacecraft and give a sense of intimacy that you didn’t get before. We are used to seeing stills of anonymous space suits with the gold visor down. I wanted the viewer to feel like they were there too, making these incredible journeys with these space explorers. You can see what the inside of a 1960s moon ship actually looks like.’

In terms of equipment, Andy was set up to do the basics, but had to upgrade some of his hardware, particularly memory. ‘I had hard drives everywhere and used lot of cloud storage as there was a huge amount of data.’ He didn’t need to go out and buy a new super-computer, however: ‘I used a quality monitor and a graphics tab but I didn’t need a super-fast computer processor – it was more about ensuring I had enough memory.’

Before and After, Apollo 9, March 7, 1969 Hasselblad 70mm. Lens 80mm F/2.8 | By Rusty Schweickart, NASA ID: AS09-24-3665. A studio-like portrait recovered from underexposed film reveals McDivitt undertaking the world’s first docking of two crewed spacecraft (with internal transfer). As McDivitt looked up, he had to translate the LM’s controls by 90 degrees in his head –Schweickart told me this was “an almost impossible task.” The reflection of the docking window, Earth and COAS (guidance) sight can be seen in his “bubble” helmet. This is the only photograph of an Apolloastronaut in their full suit and “bubble” helmet during flight. ©NASA / JSC / ASU / Andy Saunders

Andy used a Mac for converting the movie footage into individual frames, but did all the editing on a PC. ‘I eat up 10TB of hard drive storage and a similar amount in the cloud. In hindsight I would have liked more RAM, it would have made the process faster.’

Stacks of time

Software-wise, Andy didn’t have to develop any programs himself and mainly used Lightroom and Photoshop.

‘I avoided any AI-based software or processes, however, as I didn’t want a computer program to invent pixels for me. I wanted an absolutely accurate record. For the stacking, you can even use free software, but I had to stack each frame manually in Photoshop, which was very time-consuming and certainly not for the faint-hearted. It could take a couple of days to do the stacking for just one image, particularly those which were underexposed – and a lot of them were.’

For the 16mm movie footage, Andy’s stacking technique (often used in astrophotography), involved separating individual frames and aligning and stacking them in order to reduce noise. He had to develop his own technique to deal with all the camera movement in the frames, the details of which he’s keeping close to his chest for the time being.

In addition, Andy worked on the scans of still images taken by the astronauts on a range of Hasselblad cameras. A digital scan of a 70mm Hasselblad frame delivered a 1.3GB, 16-bit TIFF file, which is 11,000 pixels square. This sounds a lot, but Andy was still dealing with a digital scan of old analogue film.

Again, Andy won’t go into masses of detail, but the editing process involved carefully bringing up areas of low contrast and a lot of noise reduction. He also removed artefacts that slipped through the film cleaning process before it was scanned by NASA.

The Cameras Taken There

Hasselblad camera.

As Andy explains, despite the Apollo missions being a patriotic, all-American effort to beat the Soviet Union to the moon, they didn’t only use American photographic equipment. ‘NASA mainly used Swedish Hasselblad cameras with East German Carl Zeiss lenses, while Kodak provided the film. They went with the best equipment they could find.

One of the early Project Mercury astronauts, Wally Schirra, knew a lot of the top news photographers at the time and championed the use of Hasselblad medium format gear. Schirra dropped into a photographic store in Houston and bought a Hasselblad 500C off the shelf, which he delivered to NASA for a few modifications. Further experimentation ensued and by the time of Apollo 11, Armstrong and his crew were using multiple adapted Hasselblad 500 ELs.

For much more detail on the mission cameras, see our article here.

Apollo 9, 6th March, 1969, Hasselblad SWC 70mm lens 38mm f/4.5 by Rusty Schweickart, NASA ID: AS09-20-3064 Scott: ‘We’re all taking pictures of everybody taking pictures.’ This image shows much of the CSM/LM stack: Scott is in the Command Module hatch taking a picture with his Hasselblad 500C (note, front mounted shutter release and manual film advance winder) of Schweickart. Scott: ‘Hey, Rusty. Why don’t you lean over here again; I’d sure like to get a picture of that whole scene. © NASA / JSC / ASU / Andy Saunders

Andy’s workflow

‘Further culling of all the scans gave me a shortlist of images that revealed something new, of historical significance, and helped tell the story. These I processed to the nth degree. With the image of Jim McDivitt used on the book cover, for instance, I could see that the little window was underexposed and I thought I might be able to reveal another astronaut.’

It never worried Andy as he posted his enhanced images online that a big software company would muscle in, or that other image restorers would try to steal his glory. ‘I just wanted people to see what I was doing. As each Apollo mission marked its 50th anniversary, I was keen to get the pictures in the news again, and to get people talking about them.’

NASA and photography

Apollo 9, 6th March, 1969, Hasselblad 70mm. Lens 80mm F/2.8. By Dave Scott. McDivitt: ‘Oh, I’ve got to have that camera and get you! . . . In your visor, our spacecraft Gumdrop completely all the way down to the bottom of the service module and the whole Earth behind you!’ Scott: ‘Oh, hey! I got one of those too now that you mention it. Just don’t move, Russell.’ Scott’s view back at Schweickart using his Hasselblad SWC (note, top-mounted shutter release and manual film advance winder) and the LM, CSM, Scott and the whole Earth reflected in his visor. © NASA / JSC / ASU / Andy Saunders

As Andy explains, at the start of the moon mission planning in 1961, NASA didn’t have much appetite for photography – it was one man going up in a tiny capsule with no time to worry about cameras.

‘But John Glenn, who was the first American to orbit Earth in 1962, took it upon himself to buy a Ansco Autoset camera from a drug store in Florida, get it adapted and take photos on his mission. He also had a Leica supplied by NASA. It wasn’t until Gemini 4, the second crewed spaceflight in 1964, that we got photos of an astronaut (Ed White) against the backdrop of Earth, however.

This image turned out to be a real game-changer. The huge public response convinced NASA that they could use photography to get the public on board and get continued government support. By the time of Neil Armstrong’s moon landing there had been a lot of camera development and training given to the astronauts.

Some of them later told me that they were thoroughly sick of taking photos by the time they went up in space – NASA had them practising all the time, including on their vacations. So, most of the material they came back with was usable, though on the Apollo 8 mission to the far side of the moon, Bill Anders put on the wrong film magazine in error – it was very fast film designed for shooting star fields etc. He realised his mistake, told mission control, and they were able to process the film in a different way and still get something usable.’

Houston, we’ve had a problem

Before and after, Apollo 13, 15th-16th April, 1970, 1,000 Image Samples From Multiple Frames Of 16mm Film, Stacked, Processed And Stitched, NASA ID: APOLLO 13 MAG 1208. Lovell: ‘You know, we’ve gone a hell of a long time without any sleep.’ Commander Lovell (hand, left) keeps watch over his ship and crew as they try to rest in the cold, dark LM. Haise has his arm tucked away while Swigert is curled up on the ascent engine cover in the storage area; the tunnel to the CM is above him. ©NASA / Andy Saunders (Digital Source: Stephen Slater)

As well as the iconic images of the first moon landing, the remarkably candid shots of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission are another big highlight of the book. ‘I was fascinated by Apollo 13, having seen the Tom Hanks movie, and I am still amazed how calm Jim Lovell and the rest of the crew look. On some images they even look jovial.

Although the images in the book were taken after the explosion, the crew had no idea whether they would make it back home alive. Despite the danger of the moment, they took lots of images; at one point Jim Lovell ordered them to put the cameras away and focus on getting the famous ‘manual burn’ right. These were hard-nosed ex-test pilots, remember, so they’d learn to subdue emotion as it just got in the way.’

Andy finds it hard to name a favourite image, but is particularly fond of that used on the book cover, showing Jim McDivitt. ‘It has a bit of everything but essentially it shows a man doing his job in very hazardous conditions. He appears to be looking up in wonder, but is just focusing on what he needs to do.’

Apollo 14 February 6, 1971, Hasselblad 70mm lens f/5.6 by Edgar Mitchell NASA ID: AS14-66-9336 TO 9343. Back in the LM, the crew photographed the landing site just before leaving the Moon. This stitched panorama shows the scene asit would be found to this day. Mitchell’s discarded PLSS is lower left. Shepard hurled his own significantly further. The ALSEP is upper left, Turtle Rock upper center and the TV camera far right. Both golf balls are also visible (in the crater, above center, and upper left on the “lunar fairway”). (Panorama, fiducial mark removal, EL: 4/5) © NASA / JSC / ASU / Andy Saunders

The next mission

As you can imagine, Apollo Remastered soon turned into a full-time job and certainly not something you could do after a hard day at the office. Andy was in a position where he was able to put his career and business interests to one side and focus full time on this epic editing project.

‘Actually, it was beyond full time, it was a 16- to 17-hour day at one point. I’ve now become a full-time author and image restorer and want to do more remastering of images from Gemini and Mercury, the pre-Apollo missions. The astronauts on Gemini used a Hasselblad super wide camera and the results were amazing – they were predominantly of Earth, and frequently referenced by big Hollywood movies. This should keep me busy for a while!’

For Andy, the take-away message of this amazing labour of love is that we should never give up on old film images and footage, however hard enhancing them appears to be.

‘As a kid, I remember the devastation you felt when a film developer told you the film was spoilt or unusable. With today’s digital processing it is not necessarily lost for ever, however, and you can do some amazing things – so don’t throw old pictures and home movies away.’

Andy ends with a wry riposte to moon-landing deniers who say the photos and footage are faked. ‘When you see all those 35,000 scans from NASA, you realise that it would have been easier to go to the moon than to fake them all!’

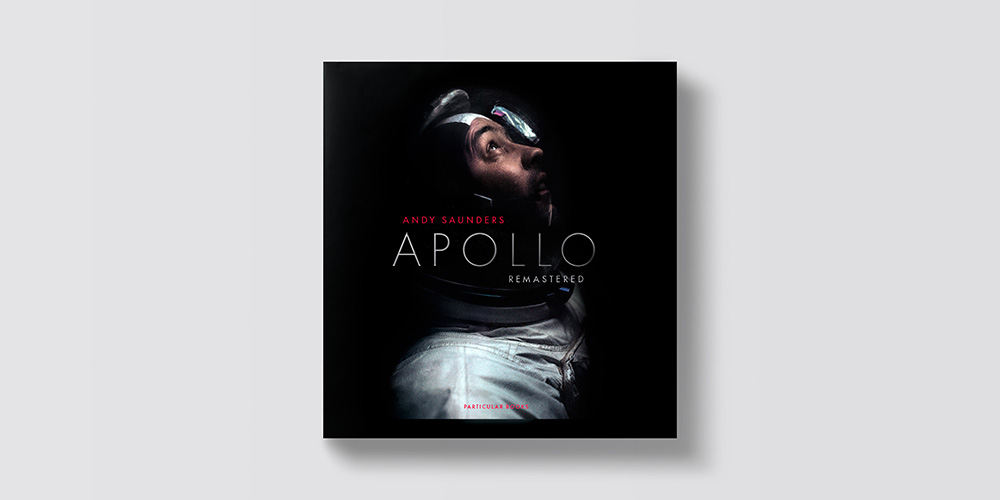

Brought to book

Apollo Remastered by Andy Saunders, Credit: Penguin Random House UK.

Apollo Remastered features over 400 full-page photographs taken during the Apollo missions to the moon. Every image has been digitally remastered from the original flight film, or HD transfers of the 16mm ‘movie’ film. The book covers every Apollo mission, as well as some of the preceding Mercury and Gemini missions that helped pave the way. ‘It’s the next best thing to being there,’ said Apollo 16 astronaut, Charlie Duke. Apollo Remastered is published by Penguin Books, ISBN: 9780241508695, and is available now for £60.

Andy Saunders

Andy Saunders is one of the world’s foremost experts on NASA digital restoration as well as being a keen photographer in his own right. His work has been exhibited at museums, and appeared in BBC News, The Daily Telegraph, Smithsonian’s Air & Space Magazine, Ars Technica, and The Washington Post, as well as in NASA’s own archives. See www.apolloremastered.com

Twitter: @AndySaunders_1

Instagram: @andysaunders_1

Related articles:

Essential guide to astrophotography

Shooting the night sky: tips from Astronomy Photographer of the Year winners

Astronaut Tim Peake chooses his best photos from space