It was not just their ‘troubles’ that many of the men – and women – who marched away between 1914 and 1918 packed into their ‘old kit bags’. Along with their absolute military essentials, they slipped another, unofficial, item into their pack or tunic pocket: the new, exciting, compact Vest Pocket Kodak camera – the VPK.

Senior officers mixing with other ranks in 1915. This picture was taken several weeks after the British Army had banned the use of cameras

Transported to battlefields around the world, these cherished VPKs were the tools by which the ordinary soldier or nurse would capture the significant events of what would be the single greatest adventure of their lives – in real time. No other army in history had been able to record its war in detail but the men and women of 1914-1918 had the technology; they had their trusty VPKs – blatantly advertised as the ‘Soldier’s Kodak’ – and they were determined not to miss a minute.

The Vest Pocket Kodak

Battlefield photography was not a new phenomenon. The first war photograph had depicted a scene from the American–Mexican War of 1846, and the photographs taken by Roger Fenton in the Crimea and Mathew Brady’s team during the American Civil War broadcast the gruesome realities of conflict to a wider audience – albeit often staged.

But such technology was cumbersome. Roger Fenton and Mathew Brady had used wet-plate technology with its associated large, unwieldy cameras that needed long exposure times. However, Kodak launched its new medium for the masses in 1912, just two years before the outbreak of the First World War. The response was astonishing. Thousands invested in the new VPK technology – smaller, lighter, portable cameras using celluloid film, which produced images of a consistent quality – and were bitten by the photography bug. A craze was born. Now, ordinary people did not have to rely on professional studios or offcial photographers as a means of recording their lives and the lives of those around them. They could do it for themselves. And so they did, in their thousands, with many soldiers among them.

Packing their VPKs, they marched off to war. They had no idea where they were going or what fate awaited them, but they would document their days and snap their deeds along the way.

Thousands of the light portable cameras made their way to Europe during the First World War

Always ready for action

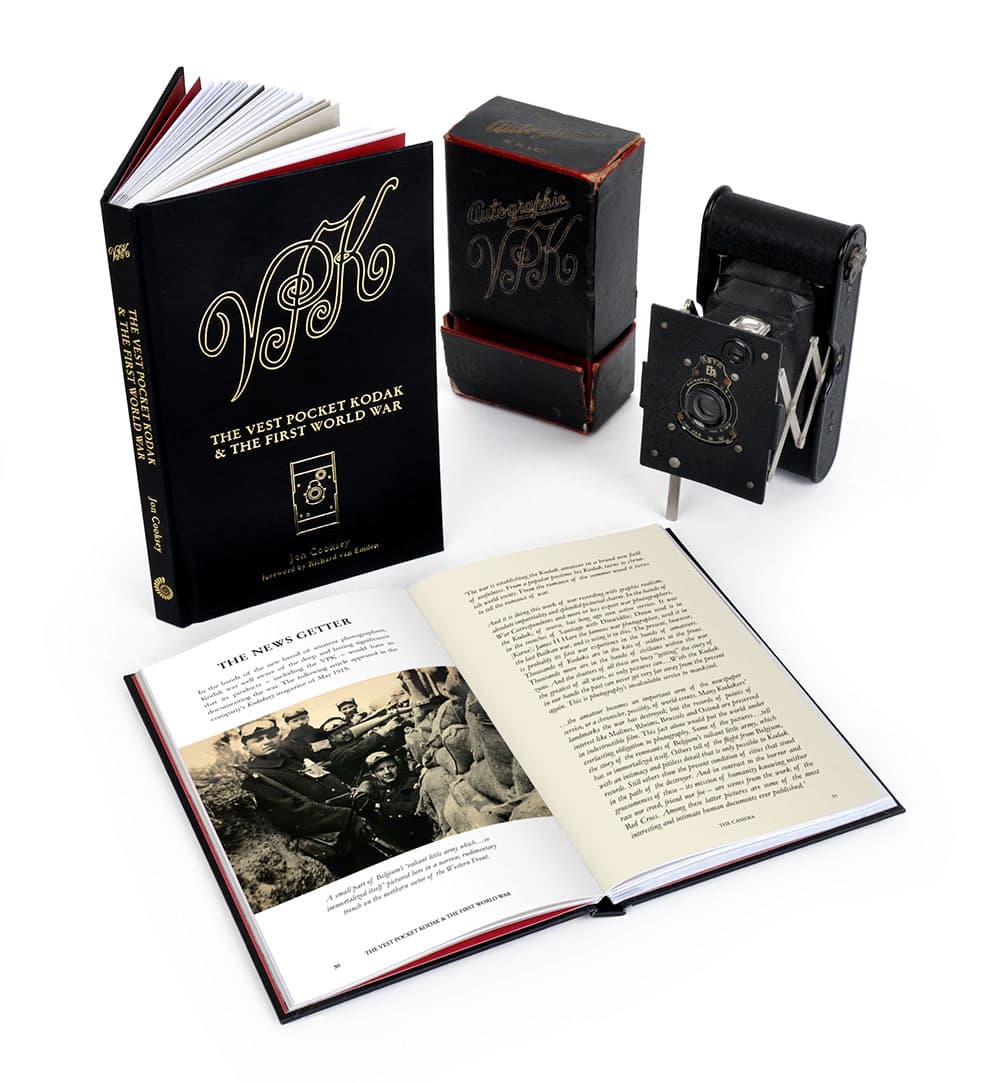

Kodak had introduced its ‘new Vest Pocket Kodak’ to the world in its catalogue of 1912. ‘This wonderfully compact little camera… is always ready for action.’ It was six years since it had ceased production of the No. 0 Folding Pocket Kodak, but the concept of its compact, built-in roll film mechanism and pull-out, strut-supported lens board were redesigned and re-engineered to fit into a lightweight, all-aluminium body, while its 15⁄8 x 21⁄2in negative format film was reconfigured into a smaller cartridge to create what would become known as the eight-exposure 127 film in 1913. The result was a smaller, more compact and lighter camera. Measuring just 1 x 23⁄8 x 43⁄4 in and weighing in at nine ounces, it was not much bigger than today’s iPhone and was instantly recognisable by its organic, curved design, shiny, black enamel finish, nickel-plated struts and black leather bellows when extended. Now, amateur photographers at the start of a the 20th century had a window through which they could capture and document their new-fangled, rapidly changing, brave new world for $6 – half the average weekly wage in the United States – or 30 shillings in Britain, with rolls of film at just 20 cents apiece. The VPK – an icon of form, function and visual democracy – was born. It was an immediate hit with amateur photographers in the US and abroad who were looking for compact, portable and easy-to-operate cameras that represented excellent value for money. The VPK revolutionised the possibilities and scope of amateur photographers worldwide and contributed to what became almost a craze in Europe in the two years prior to the outbreak of the First World War. By 1914, yearly sales of the VPK in Britain reached 5,500.

Lieutenant Harry Colver of the 1/5 York and Lancaster Regiment (right) poses with fellow officer Lieutenant Alfred Carr on York station platform, in April 1915, as they wait for the train that will take them to Folkestone on the first leg of their road to war

Great adventure

When war broke out in August 1914, hundreds of British soldiers took their VPKs to France in what many expected to be a short but glorious war of adventure. Their hope was to capture on film, for posterity, their part in what they sensed would be the greatest test of their lives, just as they had snapped their escapades on holiday in peacetime. Understandably, given such an existential crisis, the popularity of the amateur photography craze amongst the soldiery was not a high priority at the War Office, and the wisdom of soldiers taking their own cameras to the front was never questioned. With no-one checking on the numbers of cameras carried – more often than not by officers – or the content of any photographs taken, the men of the British Expeditionary Force began snapping away immediately, charting every twist and turn of the embarkation, the channel crossing, the march to the front and eventually the fighting. Many officers, some of them holding very senior positions in regular British infantry battalions with long and illustrious records, documented the early months of the war in great detail – from the first engagements at Mons and Le Cateau in August 1914, throughout the Great Retreat, the battles of the Marne and the Aisne in September and the onset of trench warfare during the winter of 1914-1915.

Men of the 1st Battalion East Lancashire Regiment take cover on a hillside south of Solesmes, France on 25 August 1914. Photograph taken by battalion second-in-command Major Thomas Stanton Lambert

Action shot

The first uncensored ‘action’ shot of the war – the transport column of the 1st Battalion the Middlesex Regiment under shell re on the high ground south of the River Marne, complete with wounded and bleeding officer – appeared in the new wartime weekly The War Illustrated on 21 November 1914. Fearing the potential intelligence and propaganda value should soldiers’ photographs fall into the wrong hands, the British Army issued a General Routine Order (GRO) before Christmas 1914: ‘The taking of photographs is not permitted… Any officers or soldier… found in possession of a camera will be placed in arrest, and the case reported to the General Headquarters.’

Images of British soldiers openly ‘fraternising with Fritz’ in no man’s land at Christmas 1914 rocked the authorities when they appeared in the press in January 1915. A catch-all War Office Instruction (WOI) was issued in March 1915, banning the possession and use of cameras in all operational theatres. Many officers and men duly sent their cameras home, but some continued to snap away, oblivious to, or in spite of, the warnings and often with the collusion of their superiors. Some continued to use their VPKs throughout 1916 into 1917 and even 1918. Their images – taken by, and of, ‘everyman’ and ‘everywoman’ at war – would forever link the Vest Pocket Kodak to the first ‘Great War for Civilisation’.

The 1912 launch of the Vest Pocket Kodak sparked an unprecedented craze for photography

The Vest Pocket Kodak & the First World War by Jon Cooksey, is published by Ammonite Press, £7.99, ISBN 978-1781452790.

Jon Cooksey is a military historian who has worked on radio and TV documentaries such as Heroes at War (BBC Radio 5 Live). He is the author of 20 titles, and has written for national magazines and newspapers.