Like many children who watched ‘Eagle’, the lunar module from Apollo 11, land on the Moon in 1969, Pete Lawrence found himself looking skywards and wondering what lay beyond his natural

vision. To satisfy his curiosity, his parents bought him a 40mm refractor telescope, and he was soon peering through the glass at Saturn, some 1.2 billion kilometres away. His next telescope was a cheap, home-made affair – he even ground the main mirror himself – and gave surprisingly good results. Encouraged by these early experiments, Pete went on to study physics with astrophysics at the University of Leicester, before becoming heavily involved in computer software development.

In the late 1990s, Pete decided to combine his computer know-how with his passion for astronomy by taking up astrophotography using a digital camera. ‘One night, I was out with my telescope looking at the Moon, and I thought I would try my luck and point the camera down the eyepiece,’ he recalls. ‘I got a pretty decent picture, and from then on my wallet has been pretty empty!’

Pete’s images have been published widely, and in 2014, he was awarded the Davies Medal for ‘significant contribution in the digital field of imaging science’ by the RPS. His expertise has led to significant presenting roles on the BBC programme The Sky at Night, as well as regular consultation work for the BBC’s Stargazing Live.

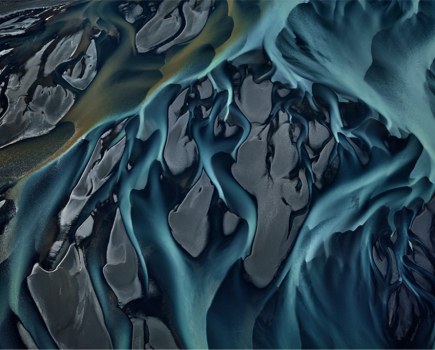

The splendour of the Milky Way’s core, photographed from the Atacama Desert, Paranal, Chile

Prize-winning picture

It’s fitting, then, that Pete has served on the judging panel for Insight Astronomy Photographer of the Year for eight years. ‘Every year the quality of entries is incredible, but I’m looking for something that makes me gasp,’ he explains. The panel includes astronomers, as well as experts in art and science. ‘There are quite a few of us, and there are quite a few arguments,’ he laughs. ‘Ultimately I think we all learn something from each other.’

This year’s winning image by Yu Jun of China shows an effect known as Baily’s beads, created by the Moon passing in front of the Sun during a total solar eclipse. It was a popular choice with Pete. ‘I’ve seen similar attempts at this type of picture, but I’ve never seen it done this well,’ he enthuses. ‘Often you look at a sequence like this and you know something is wrong – maybe the images are misaligned slightly – and you lose confidence in the work. But here everything is perfect; it’s a joy to look at.’

Grand Prize and Our Sun category winner, ‘Baily’s Beads’. Image by Yu Jun

The basic approach

To achieve this level of perfection Yu Jun used a Canon EOS 5D Mark II with a Sigma 150-600mm lens, and an aperture of f/10. The final result is a composite of multiple /1,600sec exposures. Many of the winning and commended entries were taken using cameras attached to telescopes, but Yu Jun’s entry is proof that striking results can be achieved using a pro-spec DSLR and telephoto lens. ‘There is a huge range of equipment available for astrophotography,’ explains Pete. ‘But simple pictures of the Moon rising above foreground scenes are achievable with relatively basic kit – even a smartphone pointed down the eye of a telescope can yield decent results.’

The equipment and approach required depend on the subject you are trying to capture. Shooting the Moon, for example, requires little more than a DSLR (with a high- frame rate) and a telephoto lens of 250mm or more. But to capture maximum detail you also need a long focal length telescope, and an equatorial mount (which has one axis aligned to the celestial pole). Next, you need to find a spot that allows an unobstructed view of the Moon, as far away from buildings and sources of light as possible.

‘The litmus test for a dark sky is whether or not you can see the Milky Way,’ says Pete. With the location and gear sorted you need to select a low ISO (to avoid excessive noise) and experiment with shutter speeds of around 1/30sec (underexposing slightly to avoid blowing out the highlights).

A single 420sec exposure of the Pleiades, of Seven Sisters, open cluster

Acceptable post-processing

Naturally, the files produced require a fair amount of post-processing, and Pete has his own views as to what is acceptable with regards to the competition. ‘If you’re pulling out details or trying to show information that is already there, that’s fine,’ he says. ‘But you need to be honest. There are a lot of experts out there and they pick up on these things very quickly. I’ve even seen images where people have grabbed shots from Hubble and blended it with their own picture, but this is a pretty extreme example!’

Pete has noticed a growing interest in astrophotography in recent years, which he attributes to TV programmes as well as media interest in the mission of British astronaut Tim Peake. ‘When people buy a telescope now, their first question is often: “How do I attach a camera to it?”’ he says. Having attached his own camera to a telescope for many years, it would be easy for Pete to become jaded. ‘After a while you have to develop a coping mechanism to deal with what you are experiencing,’ he admits. ‘The distances and vastness are so immense that you can easily become desensitised. There is a slight sadness about that, because I can still remember the excitement and energy of those early days. But the passion is still there; it has just shifted to a different place.’

About Pete Lawrence

To see more of Pete’s work, visit www.digitalsky.org.uk. For details about the competition, including advice on shooting astronomy pictures, visit www.rmg.co.uk. Pete was featured in the film Slow Time in association with Leffe beer – to see the video, visit YouTube.