NB. This article contains references and imagery related to death and suicide.

The wife’s husband is dying because he has cancer. To get used to the idea, the wife collects his personal belongings and scatters them on the floor while he sleeps. (excerpt from Practice Items by Chiara Barzini)

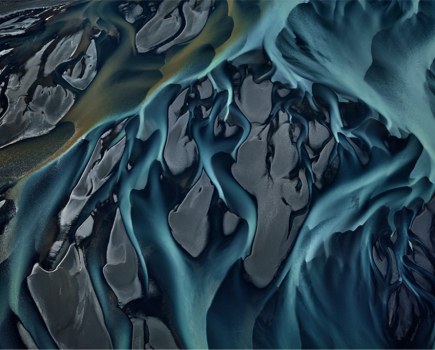

Edgar Martins, from the series Siloquies and Soliloquies on death, life and other interludes, 2016 – 01

If you are not able to define what death is, then how are you able to relate to it? This is the main idea behind Martins’ new photography project, exploring death and its depiction in the media.

Martins was able to gain exclusive access to Portugal’s Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences’ archive of photographs as well as individual police and medical case files covering the last 100 years. Alongside material from other forensic institutes, he used these collections to create a range of imagery exploring the concept of death.

Man Leaves a 1904 Page Suicide Note and Then Shoots Himself as Part of a Philosophical Exploration

Edgar Martins, Untitled from the series Siloquies and Soliloquies on death, life and other interludes, 2016.

Subject choice

His images may deal with difficult subject matter, however they do not seem morbid or exploitative. Martins’ images are presented in a matter-of-fact way, dealing with areas where death is often more openly discussed than usual – such as homicide or suicide.

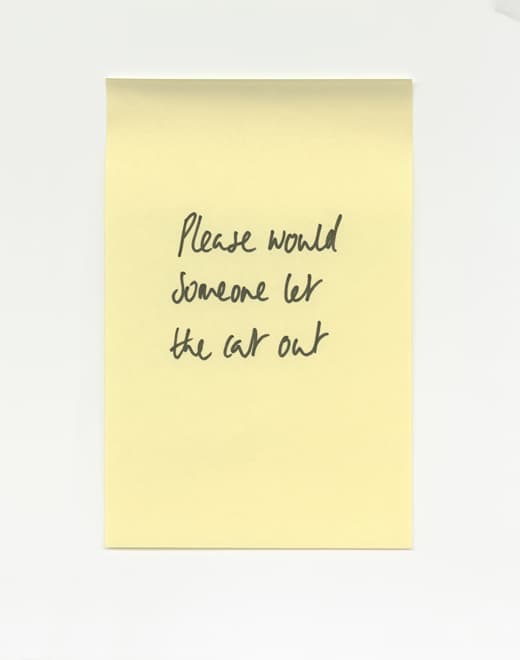

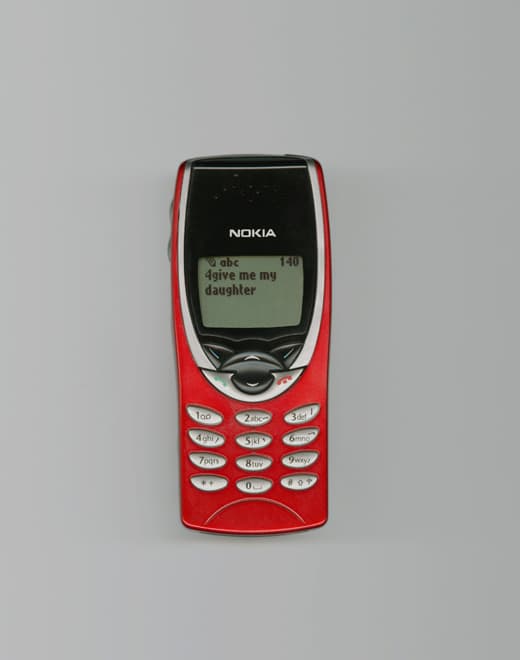

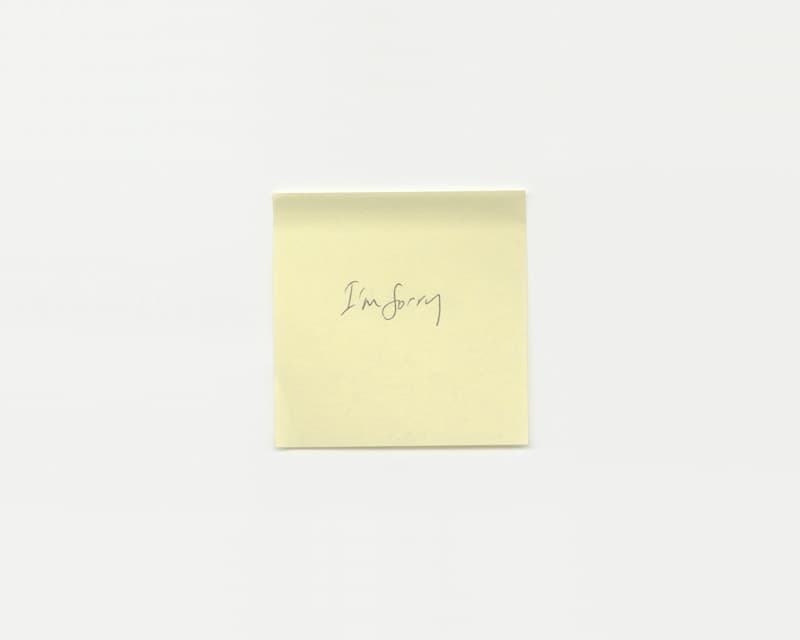

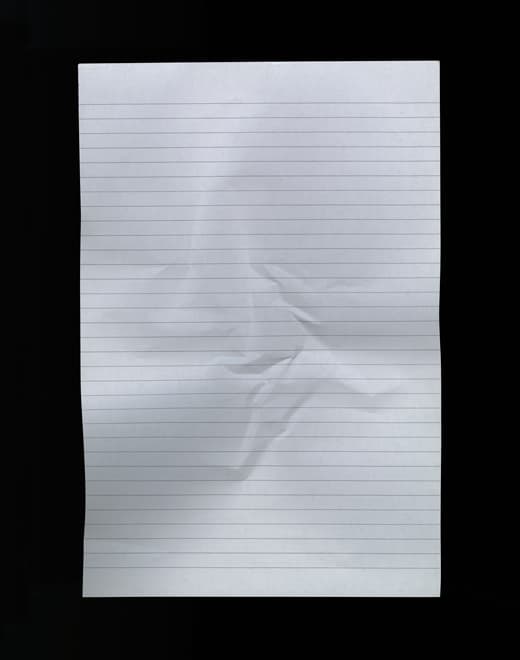

His images confront us with suicide notes folded into paper aeroplanes or sent by text; bloodied ligatures made from bed sheets and ropes; shoes and hats showing signs of violence; places that we are told are crime scenes, but that betray no signs of violence. There is much left to the imagination here, context is everything.

Instant comma. 30-35 years old. Divorced. Prostitute.

Bowler hat located in the same store room at the Institute of Legal Medicine as previous skull. Further details unknown.

‘Initially I went into the archive with the idea of photographing their collection of projectiles,’ Martins explains. ‘That’s when I became aware that they had this vast collection of suicide paraphernalia, mostly ropes. Though the ropes fascinated me, photographing them was very difficult. In some cases I was photographing the items two days after the person had committed suicide. But in a way it felt right, it didn’t feel exploitative as there was something very ritualistic about the way I photographed.’

Depicting death

Martins is not out to shock, quite the opposite. He feels too often that death is depicted gratuitously and he is concerned primarily with exploring our relationship to death and how it is depicted in photography.

‘The project is really about bringing together, exposing and holding attention to all these ideas relating to the contradictions and problems inherent in the depiction of death,’ he says.

Expanding on this idea of contradictions and problems he continues, ‘When the media talks about death, by and large the images used are gory and bizarre and you have to ask yourself what is the real purpose of this kind of imagery other than to sell newspapers. When people talk about death and depict murders, suicides and so on, the important part is always forgotten, which is how families deal with bereavement.’

Suicide by hanging of a female in Lisbon, 1933.

Inspiration

For Martins his interest in this subject matter had both professional and personal connotations. He says, ‘I had always been interested in this kind of subject matter,’ he says, ‘but I had never felt the time was right to approach it.’ He tried approaching a number of different organisations but it wasn’t until he found the Institute that the project really took off.

‘In the last six years I’ve worked with a lot of organisations that didn’t have a previous dialogue of working with artists, like the Metropolitan Police and the Public Order Training Centre. It really made me aware of the rewards you can have in partnering with places like this if you’re lucky enough to be invited in.’

Cadaver of an unknown individual appears in an advanced state of decomposition. He was later identified by his shoes.” (in O Século, 04.09.1935)

This is a topic that also resonates strongly with Martins from a personal point of view, ‘I also had a personal dimension to this project,’ he says, ‘I experienced first-hand the impact of traumatic death. A friend of mine was a high-profile journalist. He wasn’t a war photographer but decided to document the war in Libya because, according to him, this was the safest war he could have covered, and then he was captured. We thought that he was taken hostage with James Foley, one of the photojournalists that was later decapitated by Isis, and two other journalists, but after a month of campaigning for his release we found out that he had been killed on the first day the other journalists were taken hostage.

‘The older you get, the more encounters you have with death and that is obviously a natural part of life, but when you experience traumatic death, bereavement is a bit different. You have this sense that something has been taken away from you, and then you deal with all the aspect of life that people normally avoid such as violence and terror and all those things.

‘On the day of his funeral, his son asked me a question about what is death and what really happened to [his] Dad, and it struck me because I didn’t really know how to answer. I’m not a religious person, so I didn’t want to say, “Your Dad’s in heaven”. I paused and that pause made me feel uncomfortable because I realised that I’d never given the subject matter any real thought. So that’s the personal dimension to the work.’

Depicting death through photography

Martins also has a strong theoretical interest in photography’s ability to depict the concepts of death. ‘I’ve always structured my practice in opposition to the way certain subject matter is exploited. Photography is a difficult medium and I have a difficult relationship to it because of its propensity to exploit, to disavow subject matter.

‘You can easily exploit situations and people’s feelings, so I’ve largely stayed away from portraying people because with a subject matter like this I was very conscious of how difficult it is to cover when you’re dealing with crimes and suicides of real people.

‘I guess photography is still very much associated with the idea of truth, and with journalism you tend to believe in the veracity of the lens. I always start at a standpoint of “There’s no such thing as truth”. No matter how objective an image may be, it’s still a point of view to some degree, so that’s my starting point.’

Part of his attraction to the archive material was the way that the subjects tied in with the concepts he was trying to get across, especially elements that deal with omission, such as suicide notes. He says, ‘No matter how much photography reveals, it always omits more. If you’re focusing on something within the image, you can’t focus on everything, so you always have to ask yourself what are you not focusing on, and suicide letters to a degree are the same thing. Essentially only a small percentage of people who commit suicide actually leave letters, and the ones that do, more often than not the letters are completely ambiguous so they don’t reveal anything about the act. I quite liked this idea of establishing a metaphor between the final letter that doesn’t reveal much and the photograph that also omits. So the letters became an important part of the project.’

Depicting death

Martins’ hope is that the project will initiate more thought and discussion about the subject matter, and the ethical responsibilities of the photographer when representing death.

‘The project provides a platform to be able to engage with people. If I were just presenting crude images of violent death, I’d put off a lot of people and do something I didn’t want to do – go down a potentially confessional and exploitative route.’

‘Photography for me has always been a medium built around conceptual tensions. Because of this it always offers me a way to bring together… almost irresolvable or difficult contradictions. Questioning, but also challenging, the viewer’s expectations and I think this project works in this way. For example, one thing a lot of people tell me is that initially they didn’t want to see the exhibition, as it seemed depressing, but then they went and found that the different stories contained within the images and text, and the relationship between the two, made it interesting. So I suppose it’s about trying to break down some barriers.’

‘One thing it’s important to understand is that I’m not trying to soften the blow, or talk about death by avoiding it altogether. The project allows the viewer to find a whole host of relationships to get at the core theme, rather than getting there through raw imagery or something that would be very difficult to engage with. Certain images can be so raw they stop you from engaging with them at an inner level.’

Edgar Martins, from the series Siloquies and Soliloquies on death, life and other interludes, 2016 – 02

Ethical issues

Depicting images associated with death, and suicide in particular, can prove an ethical minefield. During his research, Martins realised that many institutions and magazines follow specific guidelines when presenting certain types of images. He found a statistic that showed people who are prone to commit suicide are much more likely to enact copycat acts based on visual triggers. A lot of the things Martin photographed he found were potential visual triggers.

‘One of the big issues we had with the curators and directors of the gallery for the exhibition in Liverpool was to what extent the things we were showing could potentially be seen as triggers.

‘So in the context of the show at the Open Eye gallery we ended up excluding most of it because being a public gallery with an audience that consists of families and young children, the gallery was a little bit apprehensive about the potential of these things causing these triggers. Whilst I understood and respected their point of view I think everything had to be seen in the context of work.’

Flat Death, Open Eye Gallery, 2016 © Ted Oonk – 01

To tackle such a sensitive issue, Martins has also sought advice from specialist organisations dealing with bereavement and death.

‘I contacted different ethical bodies, mental health charities and bereavement support groups, just to get a sense of how I could handle the subject matter. Of course each group has different views on different things, but in the end I decided to structure my work in a way that tackled the subject matter head-on by photographing archive material, but also creating fictional images based around concrete ideas. For example, instead of actually photographing the suicide letters themselves, in some cases I just used small excerpts from the letter and recreated them, or presented blank letters with just the creases from the original letters recreated.

‘These were all ways I found to tell a story that is potentially problematic and creates a visceral reaction in people. So throughout the project I tried to create that kind of distance, so that things didn’t feel too raw.’

Spousal murder-suicide involving a firearm (6.35mm pistol) in Portugal, December 2013

‘Siloquies and Soliloquies on Death, Life and Other Interludes’ was recently exhibited as part of the Flat Death exhibition at Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool.

The book of this work will be published in September and will include contributions by Dr Timothy Secret and Professor Roger Luckhurst.

If you have been affected by any of the issues mentioned above, you can contact local support groups such as the Samaritans for help or advice.