The launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite by the Soviet Union in October 1957 jolted the US Federal Government into action, and when the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was formed on 29 July 1958… the ‘Space Race’ had truly begun. NASA absorbed and succeeded the 43-year-old National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and officially began operations on 1 October 1958.

NASA’s remit was clearly set out in the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, which stated, ‘The Congress hereby declares that it is the policy of the United States that activities in space should be devoted to peaceful purposes for the benefit of all mankind.’ In other words, NASA had no military objectives.

In its initial years of existence, NASA was busy working on two overlapping programs: the X-15 rocket-powered hypersonic research aircraft (which ran from 1959 to 1968) and Project Mercury (1958 to 1963). Mercury was previously the US Air Force’s ‘Man in Space Soonest’ program, which had the original objective of getting a person into Earth orbit as soon as possible. When the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin completed a single Earth orbit on 12 April 1961 it meant the US had, once again, failed to be first to achieve a key space exploration landmark.

Apollo 9 Command Module Pilot Dave Scott emerges from the hatch, testing some of the spacesuit systems that will be used for lunar operations. The photo was taken from the hatch of the docked Lunar Module by Rusty Schweickart in March 1969. Credit: Courtesy of NASA

Photographic policy at NASA

Since its 1958 inception NASA had taken great care to document its activities in terms of recording scientific data, but in its first three years of existence it had no clear plan for photography.

Science journalist Piers Bizony – who co-authored and edited the new book The NASA Archives: 60 Years in Space – explains, ‘Actually there wasn’t [any plan for photography]. It was the astronauts who decided to take cameras into space, and they are the ones who chose to experiment with a Hasselblad. NASA went on to value the pictorial side of its astronaut missions, but this was more of a discovery than a deliberate plan.’

It wasn’t until 1961 that the future direction of NASA – and its subsequent photographic policy – got more clarity, thanks to three key factors. First, James E Webb was appointed as Administrator of NASA in February 1961 – Webb was to prove an inspired choice. Second, in May 1961, US President John F Kennedy made a request to Congress to fund a program to land a US man on the moon before the end of the 1960s. Finally, both Project Gemini and the Apollo program (aka Project Apollo) began in 1961. Gemini was based on studies to increase the capabilities of the Mercury spacecraft to long-duration flights and was designed to be a support project to Apollo with a clear focus on extravehicular activity, rendezvous and docking. Put simply, Apollo was a manned spaceflight program that used a combination of a launch rocket (Saturn V), a Command Module (to take astronauts into orbit around the moon and then bring them back to Earth), and a Lunar Module (to land on the moon).

Gemini 11 prime and backup crews by the Mission Simulator. Pictured, left to right, are astronauts William Anders, backup crew pilot; Richard Gordon Jr, prime crew pilot; Charles Conrad Jr, prime crew command pilot; and Neil Armstrong, backup crew command pilot. Credit: Courtesy of NASA

Access for photographers

Webb quickly gave structure to NASA and expanded its facilities, including the establishment of the Houston Manned Spacecraft (Johnson) Center and the Florida Launch (Kennedy) Center. The arrival of Webb at the helm of NASA also heralded an expanded role for photography, both within and outside the agency’s operations.

Bizony reveals, ‘He [Webb] instituted a deliberate policy of inviting artists to document NASA’s preparations for space. He knew that it was important to get a creative record of these momentous events, and not just purely a technical record. Good painters, illustrators and, of course, photographers were always given an amazing degree of access and freedom of expression.’

The photographers who quickly began documenting the operations of NASA included LIFE magazine’s Ralph Morse, Hank Walker, Fritz Goro and Ralph Crane. Bizony explains, ‘Mainly this was because in those days photo-journal magazines such as LIFE had a huge audience. Colour TV did not yet dominate the media. LIFE negotiated special access, and Ralph Morse and other great photographers got through the NASA gates because of their connections with the magazine.’

Of those external photographers who were granted access to NASA Ralph Morse was the most prolific, eventually spending 30 years documenting space programs. He effectively became an insider at NASA, which gave him unique access to the agency’s projects and people. So much so that astronaut John Glenn dubbed Morse ‘the eighth astronaut’, referring to how closely Morse shadowed and photographed the training of the seven Project Mercury astronauts.

Morse was also notable for his inventions and the innovative ways he captured the development of NASA’s increasingly complex activities. For rocket launches he shot double exposures, used infrared cameras, worked with motion detectors and rigged up remote cameras so that he could photograph the rockets close up.

The coverage of NASA’s space missions also extended to the likes of legendary sports photographer Neil Leifer, street photographer Garry Winogrand and the photojournalists Lawrence Schiller and Flip Schulke. Both Leifer and Winogrand were on the ground at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to shoot the launch of Apollo 11 on 16 July 1969.

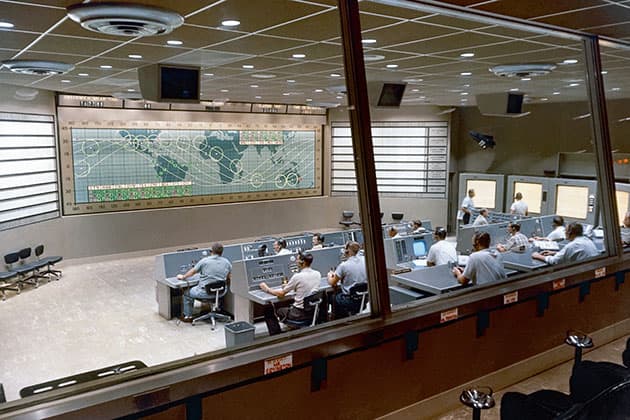

The Mercury Control Centre (MCC) at Cape Canaveral supervised seven human spaceflights between May 1961 and May 1965, into the beginning of the Gemini era. Meanwhile the more advanced control complex in Houston was taking shape ahead of Apollo. Credit: Courtesy of NASA

In-house photography

Of NASA’s in-house operations Piers Bizony reveals, ‘The agency had major photo and image archiving operations at almost all of its “field centres”, such as Houston and the Kennedy launch complex. Today these operations have been massively scaled back because the budgets are no longer there to run them. Although NASA still has huge reserves of legacy material, I have often relied on private citizen collectors for rare “behind-the- scenes at NASA” materials that were once easily obtainable from NASA.’

As well as behind-the-scenes images shot by magazine photographers and the stunning space images shot by astronauts, NASA has employed only two key in-house photographers since its inception. Bizony explains, ‘In the 1960s Bill Taub took most of the famous shots of astronauts getting ready for missions. Today, Bill Ingalls, a similarly talented photographer, does that job.’

Although Taub’s images were rarely credited by name he was often the only photographer with access to training sessions and closed engineering meetings during the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo missions. Usually one of the last people to see the astronauts before lift-off, Taub was dubbed ‘Two More Taub’ owing to his insistence on shooting just a couple more frames before the crews disappeared into their spacecrafts.

Taub worked for NASA from 1958 until 1975 while Bill Ingalls has been NASA HQ’s senior contract photographer since 1989. The 14-year gap between Taub and Ingalls holding the senior photography post at NASA was simply due to the position never being filled.

Following an internship with NASA a persistent Ingalls hounded the agency for a job. He phoned every week to see if a position was available and says, ‘I think they just got sick of me calling and said, “God. Get him a desk. Throw him in a corner.”’ Ingalls was given the choice of being a photo researcher or a photographer – he chose the latter.

Apollo 11’s view of Earth shortly before the combined vehicle left orbit and entered a trajectory for the moon. Credit: Courtesy of NASA

Ingalls was given access to NASA’s camera cabinet, which still contained much of Taub’s equipment. Ingalls once explained, ‘I’m a little bit of a hoarder when it comes to the gear. I still have everything that was in that cabinet because they have these stories that go with them.’ For example, the cabinet contained two Nikonos underwater cameras which, Taub told Ingalls, ‘were used by frogmen during Apollo splashdown recoveries’.

Both Taub and Ingalls had to deal with highly distressing assignments. It was Taub’s duty to record the aftermath of the tragic deaths of astronauts Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee and Ed White who perished, via asphyxiation, in a fire within the Apollo 1 capsule on 27 January 1967.

Similarly, in 2003, Ingalls had to photograph the aftermath of the deaths of seven astronauts when the space shuttle Columbia broke apart during its descent to Earth. This included photographing the then-NASA deputy administrator Fred Gregory making phone calls following the tragedy. When Ingalls said he felt uncomfortable at recording such moments, Gregory replied, ‘The number one thing is that people should never forget this day. It needs to be seen. It needs to be remembered – every bit of it.’

Navy divers prepare to retrieve the Gemini 6A crew on16 December 1965. Green dye was released by the spacecraft on splashdown, making it easier to spot them from the air. Credit: Courtesy of NASA

Impact of NASA’s images

The rapid development of NASA’s operations in the 1960s dovetailed with an increasing awareness of the impact of space imagery upon both the public and the budgetary decision makers in Washington DC. So how was the impact of such imagery leveraged?

Bizony says, ‘Somebody once said, “No bucks, no Buck Rogers” (it’s actually a line from the movie The Right Stuff). The scale and scope of NASA’s public relations effort in the 1960s was absolutely vast. Just imagine… they sent out tens of thousands of photographic prints and transparencies absolutely free of charge to answer almost any sensible media request. NASA knew that tax-funded space programs had to give a lot back in order to justify themselves to the public.’

He continues, ‘Apollo 8’s shots of the Earth rising above the lunar horizon have been etched into the collective human consciousness. They were seriously important in helping to inspire environmental awareness. No wonder that Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders said afterwards, “We went all the way to the moon, but what we discovered was the Earth.”’

Apollo 11 Command Module Pilot Michael Collins inspects NASA’s Lunar Receiving Laboratory, where rock samples collected by Apollo were analysed. Nitrogen gas protected the rocks from accidental corrosion in Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere. Credit: Courtesy of NASA

It was Anders who shot the iconic ‘Earthrise’ image from orbit on 24 December 1968, using custom 70mm format Kodak Ektachrome colour film and a highly modified Hasselblad 600 EL with an electric drive. In August 2003 Anders’s ‘Earthrise’ picture was included in the LIFE book 100 Photographs that Changed the World.

Yet not all NASA images have been received as warmly as the shot by Anders, with some doubting the veracity of the moon images. Piers Bizony is quick to debunk that notion: ‘In terms of astronaut photography, we hear a lot of nonsense from the moon landing conspiracy nuts that everything must have been faked because the Apollo photos are suspiciously good, as if lit in a studio.’

He adds, ‘Actually only a tiny fraction [of the images] are really worth publishing, and we tend to see the same shots used again and again, because shooting on the moon, with the sun glaring, and the surface often either blindingly bright or in deep shadow was very, very hard. Plus, of course, hundreds of images are not aimed very well because the astronauts could only point their cameras very roughly at their targets.’

Apollo1 crew members Gus Grissom (middle, centre), Roger Chaffee (second from right) and Ed White (extreme right) relax during ‘water egress’ training at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, June1966. Behind the scenes their dissatisfaction with the design of the Apollo1 spacecraft was made evident when Grissom hung a lemon over the Command Module simulator in protest. Credit: Courtesy of NASA

Advances and archives

Despite being such a revolutionary agency in terms of spacecraft technology, NASA has often relied on others for imaging technologies. Bizony explains, ‘NASA tends to adopt imaging technologies designed by other people, such as Hasselblad, Nikon or, for the robotic probes, Malin Space Science Systems. I would say that, just as there’s no such thing as “the greatest photograph ever taken”, there’s also no way to choose a greatest ever image or imaging system from among NASA’s overwhelmingly incredible history of epic explorations.’

Over 400 historic images feature in the book The NASA Archives: 60 Years in Space, which is an in-depth visual and textual record of the first six decades of the agency’s operations. Bizony reveals, ‘There were plenty of lively discussions about image choices, because we all had our favourites. We had to choose around 400 from a potential list of 3,000 that we had archived and prepared. That was very tough, having to let go of so many fabulous images because we simply couldn’t have fitted them all in.’

Of the book, Bizony sums up, ‘It’s a reminder that the USA is capable of stunning and uplifting achievements that benefit the entire world. Looking at America today, you have to wonder if it is still capable of something like Apollo or perhaps it is a nation in decline? It’s always important to remind people of what is possible, so that at least they can dream of extending what’s already been done and pushing onwards to new adventures, both in space and on the ground.’

NASA scientists are confident that Buzz Aldrin’s boot prints are still as sharp and distinct today as when they were first stampeddownin1969 because the moon has no air or rain to erode them. Credit: Courtesy of NASA

Piers Bizony is a science journalist and author who specialises in writing about outer space, space history, special effects and technology. He has written over 15 books and for publications such as The Independent, BBC Focus and Wired

The book The NASA Archives: 60 Years in Space, co-authored and edited by Piers Bizony, was published in June 2019 by Taschen (ISBN: 978-3-8365-6950-7) with an RRP of £100.