I have listened to the bugle call of the Last Post ceremony in Ypres, heard birdsong echoing around the gigantic Thiepval Memorial to the Missing and seen massed ranks of headstones that literally stretch to the horizon. But the sight of graffiti left by soldiers on cave walls has been the most poignant experience of my many trips to the former battlefields of the First World War.

A few weeks ago, as part of a photographic project, I gained access to a rarely visited network of secret tunnels and caves under the village of Bouzincourt on the Somme, dug in the 16th century as a refuge from pillagers.

A passage leads down from the village church into the tunnels 12 metres below. I was handed a hard hat because the roof is so low that you have to crawl in some places.

Our torches pierced the blackness to reveal scores of names, ranks and service numbers, intricate regimental insignia and portraits pencilled into the chalky rock, some so well defined that they might have been written yesterday – not 103 years ago.

Descendants have been travelling to Naours to find traces of their Australian ancestors. Credit: David Crossland

They tell stories of hope, fear, doggedness and pride. They are attracting increasing attention from archaeologists, historians and descendants of the soldiers who fought and died in the trenches above.

Here, in 1916 during the Somme battle in which the British army lost almost 20,000 men on the first day alone, thousands of British, Canadian and Australian soldiers sheltered, sometimes for days at a time.

‘They knew they might die,’ said my guide, Jean-Luc Rouvillain. ‘I think they left these messages so that one day their children or grandchildren would come and see them.’

One poem written by a soldier from the Highland Light Infantry starts with the line: ‘Halt the Greys, Steady the Bays and let the HLI march past.’

Black humour rings out in the proclamation ‘Here’s joy forever’ etched into the wall. One cave was turned into a chapel with a small cross carved into the rock. Next to it, the words ‘Welcome Home’ are written.

Rouvillain, of the Bouzincourt heritage society, said 2,100 soldiers’ names have been found in the tunnels. All have been photographed and logged.

There was no time to work with a tripod. I had to rely on a small LED light and put up with speeds as low as 1/10th of a second, so I shot series at 8 frames per second to make sure at least one would be sharp. I had to use ISO 3200. Thankfully, my camera was light enough to hold with one hand while I moved the light around with my other to pick out the messages.

Equipment found in the tunnels. Villagers have found ammunition, helmets, rifles, tins for bully beef and jam, and even a toothbrush. Credit: David Crossland

Uncovered stories

Like every headstone, each pencil inscription tells a story, but it does so more vividly because it was scribbled by a soldier who had dreams of a future and hopes of surviving the war – and who was well aware of the odds.

When they wrote them, they didn’t know how their story would end. We do. Their fate is coming to light as research into Bouzincourt and other forgotten places intensifies.

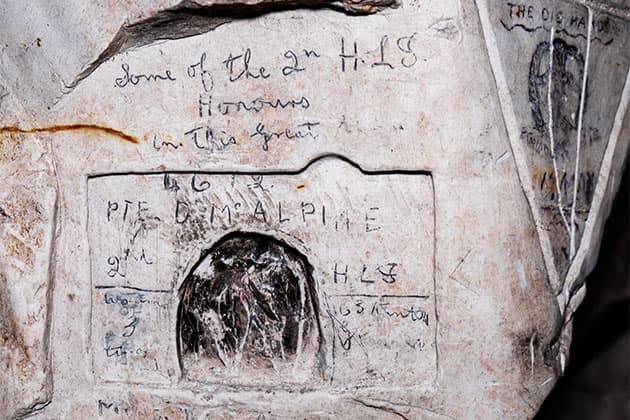

Private Daniel McAlpine, of Glasgow, wounded three times. According to the Commonwealth War Grave Commission’s website, he died on16 July, 1917. He was 20 years old.

A rectangle is carved into the wall to hold a postcard. Inside the rectangle is the number 4612 and the words ‘Pte D. McALPINE,’ ‘2nd HLI,’ ‘Wounded 3 times,’ and ‘Glasgow’.

Tragically, the website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission states that Private Daniel McAlpine of the 2nd Battalion, Highland Light Infantry, service number 4612, died on 16 July, 1917. He was 20 years old. He lies at Woburn Abbey Cemetery in Cuinchy, 60 kilometres north.

Soldiers on all sides left graffiti. At Naours near Amiens, hundreds of Australian soldiers visiting the town’s underground city while on leave – as tourists, so to speak – wrote their names. Near Nouvron-Vingré, a French soldier carved a spectacular bust of the national symbol, Marianne.

As I handed back my hard hat and dusted the chalk off my coat, I asked Monsieur Rouvillain what he found most striking about the treasure trove beneath his feet.

‘In all the writing and all the sculptures, there is no hatred,’ he said.

An impressive carving of Marianne, the French national symbol, found in the caves of Confrecourt near Nouvron-Vingré. Credit: David Crossland

David Crossland is a British freelance journalist and photographer living in Berlin. He has written three novels and is working on a non-fiction book on Western Front sites. The Bouzincourt photos were taken with a Fujifilm X-T30 and Fujinon 18-55mm lens. Illumination came from a small Aputure Amaran AL M9 LED light mounted on the hotshoe and occasionally handheld to provide oblique illumination. ISO was set at auto, maximum 3200. He says, ‘I left my DSLR at home for this trip and didn’t regret it.’