Terence Donovan’s editorial photography captured the 1960s’ spirit like nobody else, photography historian Robin Muir tells David Clark.

What is fashion / editorial photography?

Editorial photography is photography commissioned for print and online publications to help illustrate articles. This includes magazines, books and the features (i.e., not hard news). Fashion photography refers specifically to the genre of photography which is devoted to displaying clothing and other fashion items and often overlaps with editorial photography.

What is the difference between fashion, editorial and commercial photography?

Editorial and commercial photography regularly coexists on the pages of a magazine for example. Think of the photos on the ads in a magazine. The term commercial photography basically refers to photography that is created to sell something and generate profit for an individual or company.

In fashion magazines the line is quite blurred and there often isn’t much difference in style between the ad and editorial photos, except that the advertising photographers tend to be paid more. On the other hand, editorial photographers are credited with at least a by-line whereas most of the advertising photos are anonymous and uncredited.

The best of times: Fashion photography in the 60s

In the early 1960s, fashion photography went through a revolution that was led by three young and ambitious photographers: David Bailey, Brian Duffy and Terence Donovan. Talented and determined, with a fresh and informal style, they quickly usurped established fashion photographers such as Cecil Beaton and Norman Parkinson.

‘Before us, fashion photographers were tall, thin and camp,’ Duffy famously commented. ‘We’re different. We’re short, fat and heterosexual.’ Beaton himself later praised ‘The Terrible Three’, as he called them – ‘three cockney boys who rushed out of the somewhat staid John French’s darkroom and gave a signature to their times.’

Actually they weren’t all cockneys, nor did they all work at the studio of fashion photographer John French, but their photography did embody the freewheeling spirit of the ‘swinging sixties’.

All three went on to have successful careers in commercial and editorial photography. Today, Bailey is still active in his late 70s, while Duffy abandoned photography in the early 1980s, long before he died in 2010. Meanwhile, Donovan’s career included fashion and portraiture, as well as directing pop videos and thousands of television commercials. His reputation for excellence led to him being nicknamed ‘The Guv’nor’.

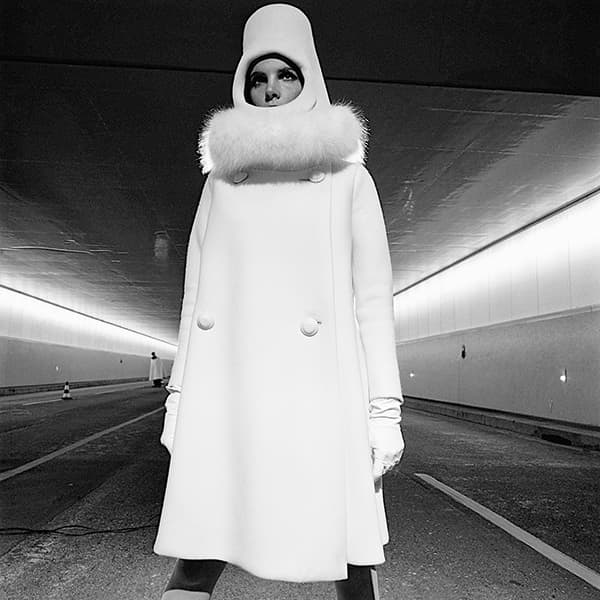

French Elle, 1 September 1966 ‘Du Nouveau sous le nouveau tunnel’. Fashion by Pierre Cardin. © Archives Elle/HFA

The year 2016 is both the 20th anniversary of his death and the 80th anniversary of his birth. These anniversaries are being marked by a new book, Terence Donovan: Portraits, and a major exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, titled Speed of Light. The exhibition is curated by photo-historian Robin Muir, who worked with Donovan at Vogue magazine and is an expert on his photography.

For Muir, the work Donovan produced in the first decade of his career was undoubtedly his best. ‘His photographs for me are just fascinating documents of the ’60s,’ he says. ‘Between 1959 and 1969 he was just absolutely at the top of his game. His pictures give us a wonderful take on London and the fashion and people of the time.’

In those early years, Donovan’s work for magazines such as Man About Town or Vogue had a gritty, street documentary style. He photographed glamorous models in the latest fashions in outdoor locations such as blocks of council flats or in parts of London still derelict from wartime bomb damage.

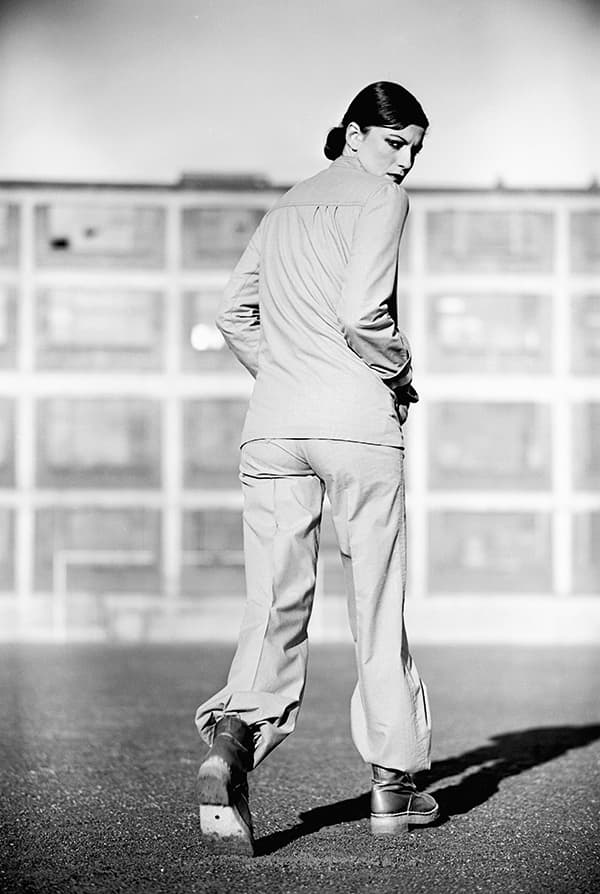

Donovan was particularly innovative in the way he photographed men’s fashion. As he himself said, ‘Up until then, all the pics of men in tweed coats had them on shooting sticks in Hyde Park. I shot them on a gasworks.’

Muir says, ‘Donovan was a fantastic photographer of men and men’s fashion, and he did a lot of wonderful black & white pictures depicting men’s clothes. He took them into parts of the East End he knew and put them into these extraordinary backdrops. Nobody else was doing men’s fashion in that way. And he did it very well. He was as good in the open air as he was in the studio and you can’t often say that about photographers.’

An authentic editorial photographer

But what else sets Terence Donovan’s editorial photography apart? ‘As the ’60s gained momentum, a lot of his contemporaries’ work became much more polished and glossy,’ says Muir. ‘Whereas although Donovan did a lot in the studio, there’s a certain sort of naturalness about it. His work looks more authentic, more honest. It just looks different. That quality lasted the whole decade.’

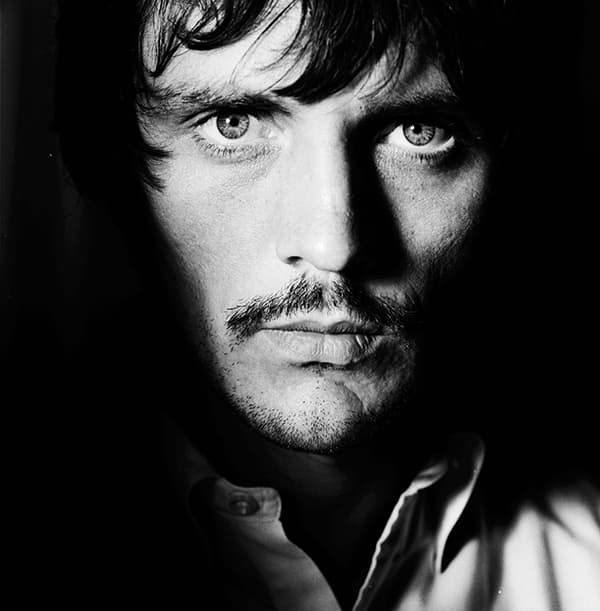

Terence Stamp, Vogue, July 1967. Photographed on the set of John Schlesinger’s Far From the Madding Crowd © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd

Donovan certainly worked hard, sometimes shooting three or four sittings a day, and was soon established as a leading fashion photographer. However, in the 1970s, he began to work much more in the lucrative worlds of print advertising and television commercials. From this point on, Muir believes his work lost something of its appeal.

‘Photographers have to mature and change, but I got the impression that Donovan’s heart wasn’t really in editorial photography any more,’ he says. ‘I think he lost his way a little bit when he discovered moving film and advertising. There was big money in advertising and you can’t blame him for wanting to go in that direction. It didn’t demand much from him in the way that earlier editorial photography had. Notwithstanding, he still produced a lot of wonderful stuff in the ’70s and ’80s.’

‘Dressed Overall’, Fashion Feature for Nova, March 1974 © Terence Donovan Archive

By the mid-1980s, Donovan had been away from regular editorial photography for so long that he was often overlooked for commissions. However, his reputation for taking definitive and iconic photographs led to commissions for official royal portraits, including a number of sittings with Princess Diana. He was also chosen to photograph Margaret Thatcher while she was prime minister.

Muir, who was present at some of Donovan’s portrait sittings for Vogue in the 1990s, says by this time his portraits were done as quickly as possible. ‘He was as charming as everybody said he was, delightful, and a very good photographer,’ Muir recalls, ‘But he had got his portrait photography down to a very fine art and a very quick art. There was no hanging around, no analysing what we were about to do; he just did it. Everybody was in and out in probably about an hour.

A suit by Hussein Chalayan, British Vogue, ‘Made in England’, 1995 © Terence Donovan Archive

‘I thought it was extraordinary, because with other photographers like Snowdon and Albert Watson there would be a lot of preparation, and a lot of chatting before the day. Terence got past all that and went straight into the photographs. I’m not sure whether that in itself was a good or bad thing, but the pictures he took latterly at Vogue weren’t among his best.’

Nevertheless, Donovan was to have one memorable return to form in 1996 when he was commissioned to photograph major music stars of the day, including Jarvis Cocker and Bryan Ferry, for GQ magazine’s ‘Cool Britannia’ issue.

In the Speed of Light exhibition, Muir will be devoting space to this final portfolio among more than 130 Donovan prints, together with work from throughout his career, as well as some of his sketchbooks, contact sheets, videos and filmed interviews.

Sadly, the GQ shoot wasn’t published until after Donovan’s sudden death in November 1996. For Muir, it is both a reminder of Donovan’s talent and an indication of the work he might have gone on to produce.

‘This wonderful portfolio for GQ would have been his way back into editorial photography,’ Muir continues. ‘It was an amazing roll call of the great and good of British music, and I think it would have been a great calling card. I genuinely believe it would have re-established his career, and if he was alive today he would have been a proper “grand old man” of photography.’

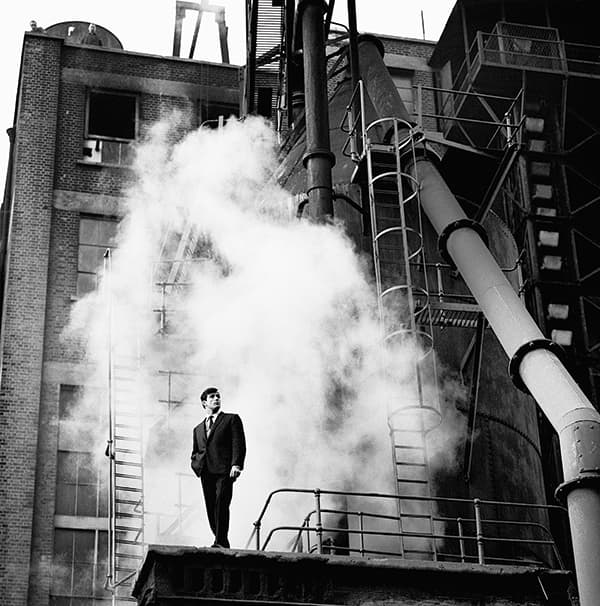

A look back: Thermodynamic, 1961

© Terence Donovan Archive

This shot was taken for About Town magazine and published as part of a fashion feature in January 1961. The model, Peter Anthony, one of the few male models of the period, was wearing a Jaeger suit. It was taken at Grove Road Power Station in St John’s Wood, London.

‘This kind of image, where Donovan has photographed his model against the backdrop of industrial London, was typical of his work in the early ’60s,’ says Robin Muir. ‘It was very dramatic to show the model against the plume of steam. Other photographers have done similar things since, but this was the first time it had been done in a mainstream magazine. There was no regard for health and safety! You couldn’t get away with it now.’

About Terence Donovan (1936-1996)

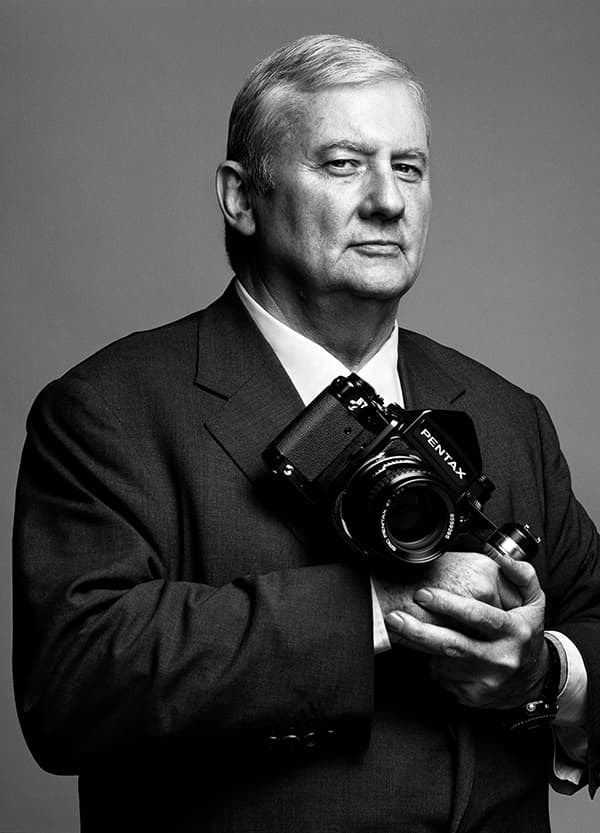

© Terence Donovan

Terence Donovan was born in Stepney, East London, in 1936. The son of a long-distance lorry driver, Donovan spent most of the Second World War travelling around England with his father. He began a part-time apprenticeship in lithography at the age of 11 and studied block making at the London School of Photo-Engraving and Lithography.

At 15, he began working as a photographer’s assistant at a printing company. After National Service, he worked at the studio of fashion photographer John French. Then, aged 22, he set up his own studio.

He shot editorial images for magazines such as Man About Town and Vogue (from 1963 onwards). He also shot fashion and portraits for Nova, The Sunday Times Magazine and others.

He concentrated on advertising photography from the early 1970s, and in the ’80s and ’90s, focused on the moving image. He shot around 3,000 TV commercials and directed influential pop videos, including Robert Palmer’s Addicted to Love.

He produced just three publications in his lifetime: the booklet Women Throooo the Eyes of Smudger Terence Donovan (1964); a book of erotic nudes, Glances (1983); and provided the images for Katsuhiko Kashiwazaki’s instructional book Fighting Judo (1985). Judo was one of Donovan’s passions, and he achieved black-belt level.

In 1996 he was appointed visiting professor at Central Saint Martins School of Art. He committed suicide later the same year after suffering from severe depression. He left behind an archive of around a million images.

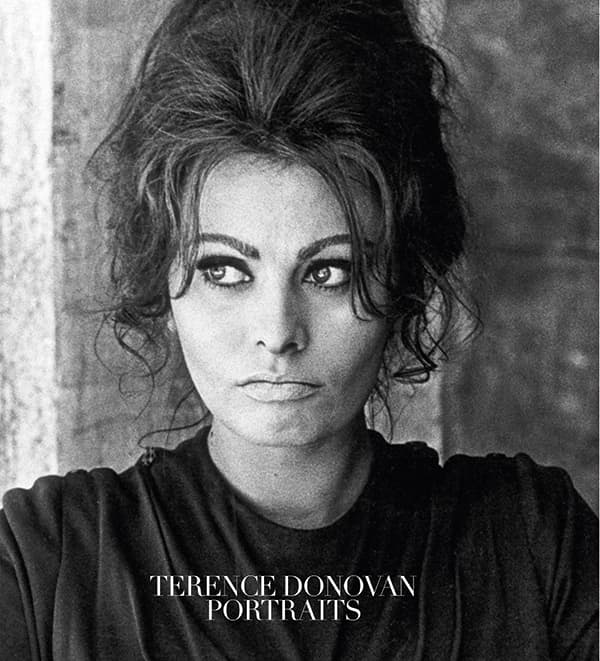

Terence Donovan: Portraits

Terence Donovan: Portraits, edited by Diana Donovan and David Hillman and featuring an accompanying essay by Philippe Garner, is published by Damiani and priced at around £35. It includes portraits made throughout Donovan’s career, including Diana, Princess of Wales; Laurence Olivier; Margaret Thatcher and Sean Connery.

Visit www.damianieditore.com for more details.

Original article by David Clark published: July 2016, updated: November 2022.