Basilica di San Giorgio Maggiore from Piazza San Marco, Venice, Italy. Taken in 1990. All images by Michael Kenna

Minimalist photography has gone from being a minority sub-genre of landscape and travel to a highly popular pursuit in its own right. And it’s not hard to understand why. As camera technology and image-editing programs get more complex by the year, there’s something reassuringly simple and uncomplicated about minimalist photography; this is image-making stripped back to the essentials, often in black & white. What’s more, it can be practised all year round, and you don’t need much more than a decent camera and tripod. However, that’s not to say that minimalist photography is easy. The masters are widely copied, but adding your own unique stamp to this type of photography is much harder.

To help you find your creative voice through minimalism, we talk exclusively to the legendary Michael Kenna.

Kenna-do attitude

Though he’d blush at the plaudit, Michael Kenna is recognised all over the world as a master of minimalist photography, particularly when it comes to landscapes. While he’s highly accomplished technically, successful minimalist photography for Michael is about much more than fretting about f-stops and filters.

‘Photography is a form of meditation,’ he explains from his base in Seattle in the USA. ‘I like to think that I could spend a day happily photographing without any film in the camera. When I photograph, I feel that I am on a treasure hunt. It is a wonderful process where we can use our sense of curiosity, respect, even reverence for the subject matter that is being photographed. Of course, having film in the camera means that I get to have belated Christmas Day presents some weeks later when I get to see the negatives back.’ Michael’s frames are as tight as a drum, and although there are few elements compared to conventional landscape photography, everything is there for a reason. There is no quick and easy formula for this approach. ‘When I photograph, I look for some sort of resonance, connection, or spark of recognition,’ he says. ‘I try not to make conscious decisions about what I am looking for.’

Each image takes as long as it takes (sometimes hours), and Michael doesn’t make elaborate preparations before he goes to a location, either. ‘Essentially I walk, explore, discover and photograph,’ he explains. ‘Approaching subject matter to photograph is like meeting a person and beginning a conversation. How does one know ahead of time where that will lead, what the subject matter will be, how intimate it will become, how long the potential relationship will last? Certainly, a sense of curiosity and a willingness to be patient to allow the subject matter to reveal itself are important elements in this process. There have been many occasions when interesting images have appeared from what I had considered uninteresting places. The reverse has been equally true and relevant. One needs to fully accept that surprises sometimes happen and control over outcome is not necessary or even desirable.’

Erhai Lake, Study 10, Yunnan, China. Taken in 2014

Hip to be square

A cursory glance at Michael’s extensive portfolio on his website reveals an enduring fascination with the square format. He claims to find the format beautiful, calm and flexible, although he’s experimented with other options, including 4×5 panoramas. The majority of his work is in black & white, too.

‘For me, black & white is more of an interpretation of the world, rather than a reproduction,’ he says. ‘I find black & white photographs to be quieter, calmer and more mysterious than images made in colour.’

The ongoing influence of Michael’s mentor, master black & white photographer and printer Ruth Bernhard, is also clear. ‘Printing in the darkroom is like learning to play a musical instrument,’ he says. ‘A few sessions and we can get the basics down, but it takes many years of hard work to be a good black & white printer.’ Michael remains wedded to film, but plays down suggestions that what he does somehow can’t be done digitally.

‘I don’t use Photoshop or Lightroom, so I’m not the best person to ask about these things,’ he says, ‘but I understand that a computer can very easily and quickly give many similar effects to what can be

achieved in the traditional darkroom. There are innumerable apps that can be applied to raw images to make them look a lot better than when they came out of the camera. As for the experience, the journey, the struggle to create a silver print, that I do know about, and recommend.’

As well as careful compositions and exquisite black & white toning, another key to Michael’s success is his consistency, regardless of the subject matter. ‘I remain pretty much the same, whether I am photographing trees, cityscapes or nuclear power stations,’ he explains. ‘I remember being criticised for photographing Nazi concentration camps in a similar style to how I photograph other subject matter. But I am who I am and I photograph in a particular way. Of course, I look for subject matter that somehow resonates with what I am interested in, so common motifs will occur.’

Michael has been a photographer for well over 40 years, so he doesn’t get bogged down in worrying about the technical side any more. ‘I don’t really do very complicated things in photography,’ he adds. ‘Generally, I am looking far more for simplicity than complication. I’ve used the same cameras for 30 years and would be happy to use them again for another 30 years. For me, they are like my paint and brushes. Why change for the sake of it?’

He is also now at the stage where he’s happy to go with the flow, rather than trying to control every aspect of a shoot to the nth degree. ‘I am a big fan of the unpredictable,’ he explains. ‘I don’t like to fully control what is happening in my photographic work. I rather like accidents. Underexposure can result in shadows dropping out and black spaces appearing – rather like Bill Brandt! Meanwhile, grain can break up an image and give a wonderful pictorial feel to it. Strong contrast can make an image look like a Mario Giacomelli picture. This is not to say that I am shoddy or lazy about my technique, however.’

Poplar trees, Fucino, Abruzzo, Italy. Taken in 2016

Editing reality

It’s easy to get the impression that Michael is like some kind of photographic Zen master, approaching a subject after meditating and then executing one, perfectly minimalist shot. The reality is somewhat different (reassuringly so for the rest of us). ‘Certainly, I over-shoot, as I never know when or if I have the best image,’ he says. ‘I constantly challenge myself to find something else. In reality,sometimes it is the first frame that is the best. But, sometimes it is the last. As I shoot film, I don’t have the benefits of seeing the results as I go along, which, to my mind, is a distinct advantage. Also, we have to remember that landscape photography is something of an editing process. We are always making decisions about what is important and significant, and how we best frame it and capture it. If we want everything, then we should just turn the video camera on and walk away.’

Michael’s signature style is instantly recognisable, and widely copied. Does he ever get bored of the square format and black & white generally – and does he sometimes feel hemmed in by the expectations of his fans?

He explains: ‘So you haven’t seen my new colour murals? Only kidding! I really don’t feel hemmed in by other people’s expectations. Of course, the classics will be appreciated more than the new material. That is normal. Viewers have lived with the images for a long time. Also, I have to say that if people think one of my images is a classic, I will never complain at all. Some of my own favourite images are from very early on. Some are also from recent projects. My best-ever image will be made sometime next week, I hope.’

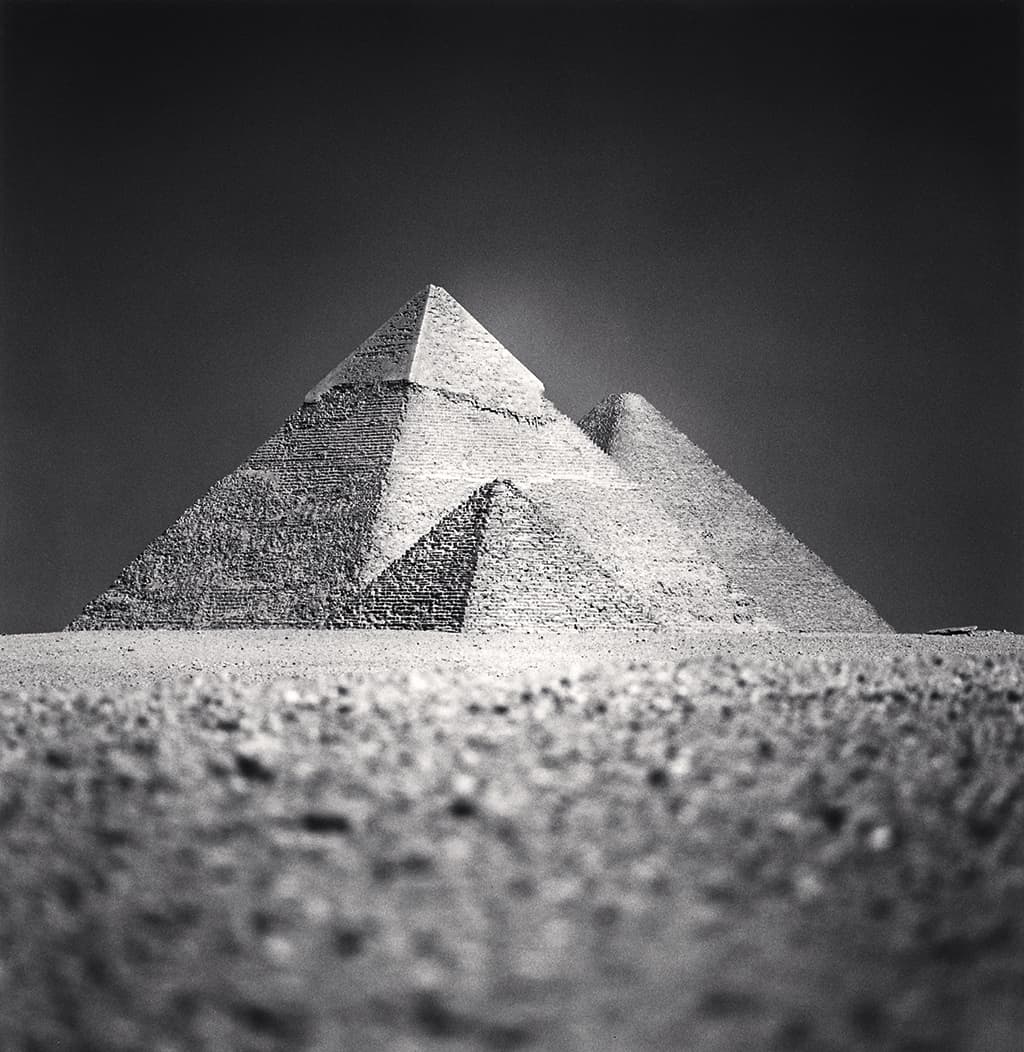

Minimalist travel

As well as his trademark landscapes, Michael is a widely travelled photographer who still manages to find fresh perspectives on shot-to-death icons such as the Giza Pyramids or the eiffel Tower. Much of this is down to his mastery of composing for the square format and black & white printing, but he’s also quite open about the influence of eastern art, where less is more – particularly the Zen-influenced art of Japan. so, before you arrive at your destination, spend some time researching how other photographers have shot the place, and how you can then strip things back for more interesting and eye-catching images.

Be more Kenna

Five tips for minimalist success

- Enjoy the creative process and be prepared to go with the flow. Be open to serendipity.

- However, never usetip1asan excuse for ‘switching off’. ‘Photography is about making creative decisions; whether you make them at the time you take the photograph or later is up to you,’ says Michael.

- Don’t get bogged down in gear. ‘The make and format of your camera is low down on the priority scale when it comes to making pictures,’ says Michael. ‘Connecting with the subject matter, and staying open and inquisitive are much bigger priorities.’

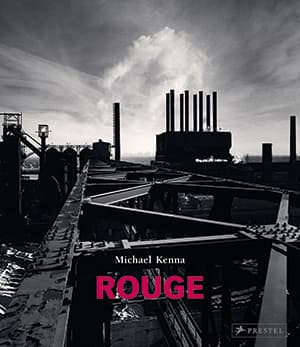

- Challenge conventional notions of what makes a beautiful subject. ‘Over the past 25 years, I have also photographed industrial environments in north-west England where I grew up, the Rouge steelworks in Detroit, USA, and coal and nuclear power stations,’ says Michael. His new book on the Rouge is on sale now.

- Get up early – Michael claims an almost mystical attachment to dawn light – and don’t try to capture everything about a subject. ‘I prefer my images to be haiku [short Japanese poems] rather than novels,’ he says.

Cloud over Uchiumi Sea, Ainan, Shikoku, Japan. Taken in 2012

Kit list

Hasselblad 120-film cameras

Michael favours two 500CM bodies with a pentaprism viewfinder.

Hasselblad lens

Although he tries to travel light, Michael usually carries five lenses, ranging from 40mm to 250mm for maximum flexibility.

Gossen Luna Pro light meter

Michael mainly uses this handheld light meter for his distinctive night exposures.

Carbon-fibre tripods

At the moment, Michael uses a range of lightweight Gitzo and Manfrotto tripods and ballheads.

__________________________________________________________________________

About Michael Kenna

Michael was born in Widnes, Cheshire, in 1953 and discovered photography at art school. After further study in London, he worked as a commercial photographer and printer before relocating to the USA. His books include Forms of Japan and Rouge, which is a study of the US industrial heartland. Michael has also exhibited widely. See www.michaelkenna.net

Michael’s latest book, Rouge, published by Prestel, is on sale now and available from all good booksellers. Price £45, 192 pages, hardback, ISBN 978-3- 79138-297-5. For more details, see bit.ly/kennarouge