Agra, 1983. A steam train passes in front of the Taj Mahal. This image would be impossible to take today. All images by Steve McCurry

Steve McCurry needs no introduction to most AP readers. He is a legendary multi-award-winning Magnum Photos and National Geographic photographer and author of its most famous cover photo: the iconic ‘Afghan Girl’.

The Philadelphia-born photographer has spent the past 40 years photographing people and cultures in every corner of the world. But there’s one place that Steve has returned to time and time again: India. It’s a country of unparalleled richness and diversity for the photographer, which perhaps explains why Steve has travelled there more than 90 times during his career. Now he has collected some of his favourite images of the subcontinent, many of them previously unpublished, in a beautiful new large-format hardback book.

AP was given the rare opportunity to interview Steve in front of a live audience in association with Nikon School Live. Here’s what he had to say about his life, career and, of course, the country that is so close to his heart.

Mumbai, 1993. Mother and child at a car window. This is one of Steve’s favourite images

Why India?

When I was about 12 years old, I read a wonderful story in Life magazine about the monsoons, by the celebrated photographer Brian Brake. I remember looking at these dramatic pictures and they captured my imagination; I was captivated by the place. So about 20 years later, when I was starting out on my freelance career, I decided to go there, and I was hooked.

In India you have all these different religions; you have this incredible disparity between the ultra rich and very poor; you have people living in villages the way they probably lived hundreds of years ago [alongside some of the world’s most populous cities]. Then there are all the festivals. The country is just an incredible array of culture. The geography is also diverse. There’s a variety of terrain and landscape. I think India has probably more depth than any other country in the world.

If you could go back one more time to only one location, where would you go?

I’d be torn between Ladakh and Rajasthan. I like the colour palette of Rajasthan, and the beautiful architecture. Places like Jodhpur and Jaipur are culturally very rich. But I’ve always been drawn to Buddhist culture, and Ladakh is just this vast expanse, with these monasteries perched on top of mountains… It has opened up to tourism a lot since I first visited India in 1978, but it’s still a wonderful place to visit.

How has India changed since your first visit?

I remember walking through these villages and being followed by 20 children because they had rarely, if ever, seen a foreigner or a photographer. Now, with the internet, cellphones and TVs, these village kids have seen everything, and a foreigner with a camera is no longer a big deal. There have been so many changes economically as well. Back when I first visited, there were only about two or three different types of cars on the roads. Today, there are huge shopping malls, just like the ones back in the United States, where there once were wheat fields. The world is becoming a lot more homogenised.

What sort of planning do you do before you travel?

I always try to hit the ground running. I try to have a translator lined up as an assistant; this is the main thing. It’s always good to have someone who can speak the local language, and who can navigate where to go and help if there’s a problem. But as far as research goes, I don’t ever want to do too much of it because, if you go with too many preconceived notions, it can spoil things. It’s more fun for me to discover things while I’m there instead of going with a long shopping list.

Agra, 1983. Women wash their clothes in the Yamuna River

What percentage of your time has been on assignment compared with being free to do your own thing?

In my career, I’d say that probably 80% of the time I was on assignment. But the most fun is to be there on my own, so I can get up when I want, shoot what I want and have no particular agenda. When you’re on assignment you have a deadline; there’s an expectation of what you’re going to do – a certain amount of pressure. There’s more planning, more research.

It’s more fun for me just to walk around and photograph whatever catches my eye and not wonder if it’s going to fit into the story I’ve been sent to tell. When I’m shooting for myself, I like to just walk out of the hotel in the morning and wander around enjoying the day, to get into the right frame of mind. Then, after a while, hopefully I start to see things. Sometimes these magic moments happen and other times I can walk around all day and not see anything. In the end, you just have to average it out. That’s why it’s important to me to be somewhere interesting, like Havana [in Cuba], or Rangoon [now Yangon in Myanmar], or India, so that if you do strike out and don’t get any good shots at least you’ve had an enjoyable walk.

What types of subjects catch your eye? What makes you take the lens cap off?

I’m interested primarily in people, and human behaviour – how people relate to each other and their environment. I’m rarely drawn to landscape photography. Landscape photography is a speciality. Rarely can you just drive down the road and see a great landscape photo; you have to plan. You need the right location, in the right light, and you need all these compositional elements.

Some people only shoot candids or posed portraits, but you seem happy with both styles. What’s your philosophy on interacting with your subjects?

For me the most fun is just to walk around unobserved and photograph life as it happens – meeting people and talking to them. It can be a little intimidating to stop someone in the street and ask if you can take their photograph. But then I see people with such interesting faces I just have to force myself to engage with them and try and convince them to let me take their picture.

You have described yourself as a shy person. Do you find stopping people gets easier with practice?

On every assignment I’ve ever done, I get to the place and after a few days, start to panic and worry that I’m not going to be able to do this and that the pictures just aren’t there. Then things start to happen and pictures start coming at me from all directions, and suddenly, everything is great.

Rajasthan, 2009. Man in an orange turban

There are certain motifs that occur frequently in your images. One of them is the perfectly framed moment where someone is walking past a gap between two buildings, or framed in a doorway. How much time will you put into waiting for that perfect moment?

Most photographers have at some time recognised a composition, perhaps a poster or something on the wall, and waited for a person or animal or car to complete the picture. There are times when you recognise a design or a composition, and you work it; if you think it’s worth it, you’ll wait for as long as it takes. I did that just a couple of nights ago in Venice. It was about 1 am and there was this amazing fog, and I waited over an hour to get the shot.

Most readers are familiar with your Afghan girl portrait and admire its intensity, but looking through your work, there are many equally powerful portraits. What’s your secret?

Often, and I’ve witnessed this in my workshops, there’s a distance between the photographer and the subject – an apprehension, a timidity; the photographers use an arm’s-length approach. They’ll take a couple of frames and then wave goodbye. I think a better approach is just to jump in head first and really try to break down that separation.

It shouldn’t be as if I’m taking something from you because you’re a curiosity and you’re odd, and I’m this rich tourist. You have to get past all of that and be like two people just hanging out. A bit of humour and some warmth always helps. Let the person feel relaxed.

Have you had any disastrous or near disastrous events in your career?

Hundreds! I always try to work with a margin of safety, but occasionally things go terribly wrong. I’ve had incidents in the past where people didn’t want to be photographed and I’ve maybe pushed things a bit too far, and realised that not only could I lose my film, and my camera, but I could also get beaten up. So I’ve learned from experience that if people don’t want to be photographed, then don’t push it.

Are there countries where photographing people is more challenging, where they’re less keen to be photographed?

For some reason Morocco has always been difficult. There are also places where people always want to be paid to be photographed, and that’s a different issue.

Rajasthan, 2002. Women in a step well

What’s your attitude toward paying for pictures?

I think it needs to be on a case-by-case basis; it’s hard to generalise. For example, take the Maasai people in East Africa. A lot of their livelihood comes from tourism. It’s the same with that square in Morocco [Jemaa el Fna in Marrakesh]. Being photographed for money is their job. So, when going into this area, you have to either accept it and pay them or not accept it and don’t photograph them. You can’t have it both ways.

What do you consider to be the ingredients of a successful picture?

It’s similar to when you hear a song on the radio. There are some songs you connect with and other you don’t. It’s the same with books and movies.

Pictures that are memorable, that stick in the mind, are the best pictures. Sometimes I’m looking at pictures and there’s nothing going on; there’s no emotion. For me great pictures are about storytelling. I want to learn something from the picture, or want it to evoke some kind of emotion. I want it to take me somewhere.

When you’re editing, do you often find that you’ll reject pictures and then go back to them later and see one that stands out, and you think, ‘Why did I reject that?’

All the time. I go back and look through my pictures, right to the beginning of my photography. By and large, I’ll be like: ‘What the hell was I thinking? This is a load of c**p!’ But occasionally I’ll find an image that I missed first time around that resonates.

One of your claims to fame is that you shot the last roll of Kodachrome 64 ever produced, and I was wondering how that came about?

I used Kodachrome for over 20 years. It was my mainstay, probably the best film ever made. They had already discontinued Kodachrome 25 and 200, so when 64 got the axe I just wanted to pay homage to Kodachrome. I had already switched to digital by this time, but I wanted to do a project with the last roll, photographing iconic people and iconic places.

I started with Robert de Niro. Then we went to India and I photographed some Indian film stars. Then I photographed some village nomads. I tried to make just one exposure per subject, which is tricky. The images are now in the museum at George Eastman House, in Rochester, New York.

West Bengal, 1983. Bicycles hang on the side of a train

Steve on his gear and career

What was your first camera?

My first camera was a Miranda. Then I switched to a Pentax and then an Olympus. When I went to India in 1975 with my girlfriend, she had a Nikon and some lenses. I thought we should just use the same camera system and share the lenses, so I switched to Nikon, and I’ve been using it ever since – different models, of course.

When did you switch to digital?

My colleagues and I at National Geographic thought we’d be able to see out our careers shooting film, even into the late 1990s. But with time, it became clear that the train was leaving the station and we’d better get on it. It was clear that this was the future, like going from a typewriter to a laptop, and you could either jump in early or late.

I love digital. I think it’s a huge leap forward in terms of picture making. I jumped in around 2005. Right now I’m using a Nikon D810, and it’s probably the best camera I’ve ever used. You can shoot in such extremely low light with it.

Some of my favourite pictures going back 20 years can’t print very big because they were back-focused. I’d be in a really dark room and I’d be shooting away thinking, ‘This is a really great picture’, only to find out when I got home later and looked at them that they were all focused on the wall in the background.

The thing with digital is that you can evaluate the focus, composition and light while you’re there. With film, you never really knew if you ‘had it’.

Do you tend to travel light or with a bag full of lenses?

I completed a major assignment a couple of weeks ago and used just a D810 and a 24-70mm lens for the entire job. I use that lens for about 98% of my work now. When I’m walking on the street, I’ll take just one body and one lens. I’ll have a back-up body and lens back at the hotel, just in case.

Steve currently uses Nikon’s 36MP full-frame D810

How has your job as a photojournalist changed over the years?

When I started, unless I was published by a major magazine, my pictures just wouldn’t be seen. It was almost impossible to get your work published. The good news is that now we can self-publish, get our pictures out on the internet, and if it’s really good people will recognise them. Today, there are much fewer assignments for the professional. But it was very tough when I was first starting too – you just have to persevere.

What advice would you give to somebody starting out now?

To become a professional photographer and make a living from it requires an enormous amount of time and effort. Unless you’re totally driven and obsessed about it, this may not be for you because it ends up consuming your whole life. If this is what you want to do, then it’s great.

Reader questions

Do you post-process your own images?

I don’t personally do the mechanics on the images, but I work closely with a wonderful printer, and together we look at a picture and decide how to manage it, just as I used to do with darkroom printers. I’m a big fan of printing my pictures, getting them on paper. We print every day.

Which was your favourite assignment and why?

The first Gulf War back in 1992 was the most profound story. The oils spills in Kuwait were an incredible environmental disaster and the amount of destruction was biblical; it was visually epic. Rarely have I been in a place that was so dramatic – it was like being in this disaster movie except that it was real.

Rajasthan, 2012. Mahouts sleep with their elephant

At which point in your life did you realise you wanted to be a photographer?

I originally wanted to be a cinematographer, and went to college to study filmmaking. On the course there was a still photography module and I fell in love with the still camera. When I left I was torn between stills and movie making and could have gone either way. What decided it was that I couldn’t get a job in the film industry, but did manage to get one on a newspaper. I’ve never regretted this decision.

Do you find it difficult to persuade people to let you photograph them?

You’re never going to get 100% of people saying yes, but I’d say I have an 85–90% success rate, which is a pretty good rate. If people think you’re sincere and your intentions are honourable, most people will give you a few minutes of their time. The thing you have to remember, though, is when you see a striking face on the street and you ask to photograph them, you don’t know their story, and what kind of day they’re having. If you’d just had some bad news and I came up to you and asked to take your picture, you’d probably say: ‘No thanks, I’m not in the mood.’ As a photographer, you can’t take it personally and get upset about it; you just have to play by the law of averages.

Do you use flash or is it all natural light?

About 99% of my work is natural light. I do carry some little portable LED lights, not much bigger than my cellphone, which I find really useful to accentuate certain things in some situations, but I only use them occasionally. I never use strobe. Not that there’s anything wrong with using flash I’m just not very skilled with it. I have used it in the past, but with digital photography now you can shoot in almost any light.

Do you only ever shoot in colour, or do you also shoot in black & white?

Well, the world is in colour, so it’s logical to me to photograph the world as it is. I admire a lot of black & white photographers, but in the kind of work that I do so much of the story – the cultural story – is in the colours, be it a Tibetan monastery or the Holi festival in India. The colour is integral.

But colour is tricky to use. It’s important to try not to let the colour distract. Sometimes there can be too much information, which is why in highly emotional situations, like war photography, it’s sometimes good to strip away this element and shoot in black & white.

Jaipur, Rajasthan 2008. Man walks through Jantar Mantar, an 18th century astronomical observation site

Do you keep all your rejects?

Yes, I keep everything. I think it’s best not to delete or throw away any pictures because you have no idea how time and history will affect how you view those pictures later. And 30 years ago, if we had images that were a little bit overexposed, we had no idea that in the future we’d be able to salvage some of those.

How do you prevent your images from being published online without your permission?

People use my pictures all over the world, all the time, without my permission. I get Google alerts telling me every day. If I found my image was being used in an ad, or on a billboard, I would of course pursue them. But if it’s just some random person using my picture on their blog, I really don’t care – life’s too short to worry about that. I’m actually kind of flattered.

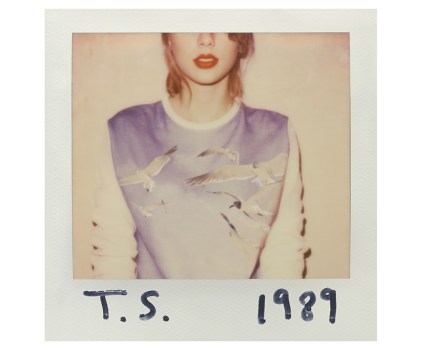

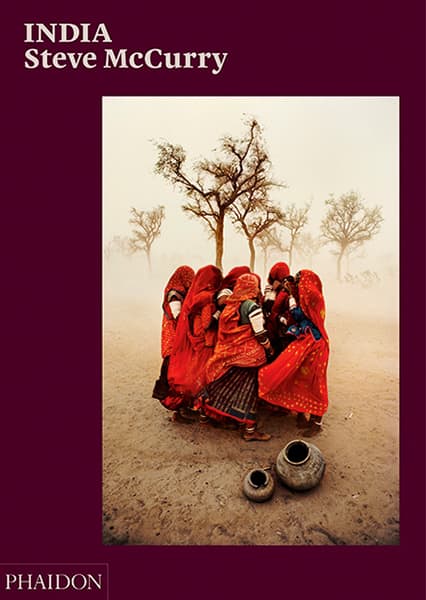

India by Steve McCurry, published by Phaidon Press, price £39.99

Reproduced in a large format, this new portfolio of emotive and beautiful work by Steve McCurry features 96 previously unpublished photos taken across the Indian subcontinent, along with images that have become known across the world.

Reproduced in a large format, this new portfolio of emotive and beautiful work by Steve McCurry features 96 previously unpublished photos taken across the Indian subcontinent, along with images that have become known across the world.

For details of other Nikon School courses, workshops and events please visit www.nikon.co.uk/training