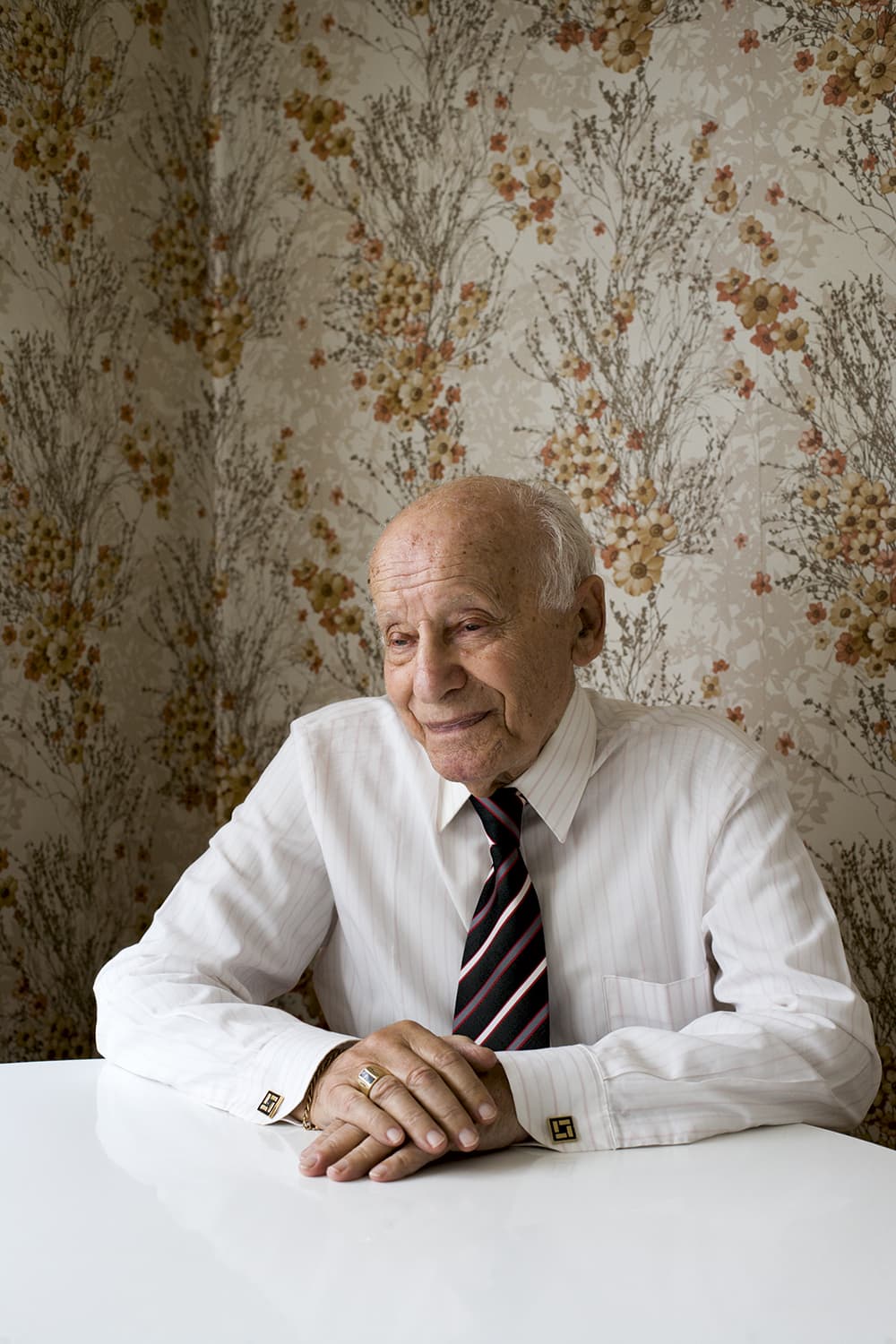

Svi Sharp. ‘My name is Hersek Szarfsztum. Born 3 March 1928 in Ryki, Poland, I am proud to be a Jew.’

Growing up on a farm in Devon in the 1970s, Harry Borden became aware that his cultural identity was different to his school friends. Although brought up in a ‘vaguely non-religious’ family with a Christian mother, his father, Charles, is a Jewish New Yorker of Eastern European descent. At a young age, Harry was shocked when his father said the Nazis would have killed him and his children for their racial background.

At the same time, his grandmother made him feel proud of his Jewish roots. ‘She pointed out the disproportionate number of famous and successful people who have Jewish ancestry,’ Harry says. ‘As I grew up, having Jewish roots didn’t impact on me on a day-to-day basis, but I was always aware of it.’

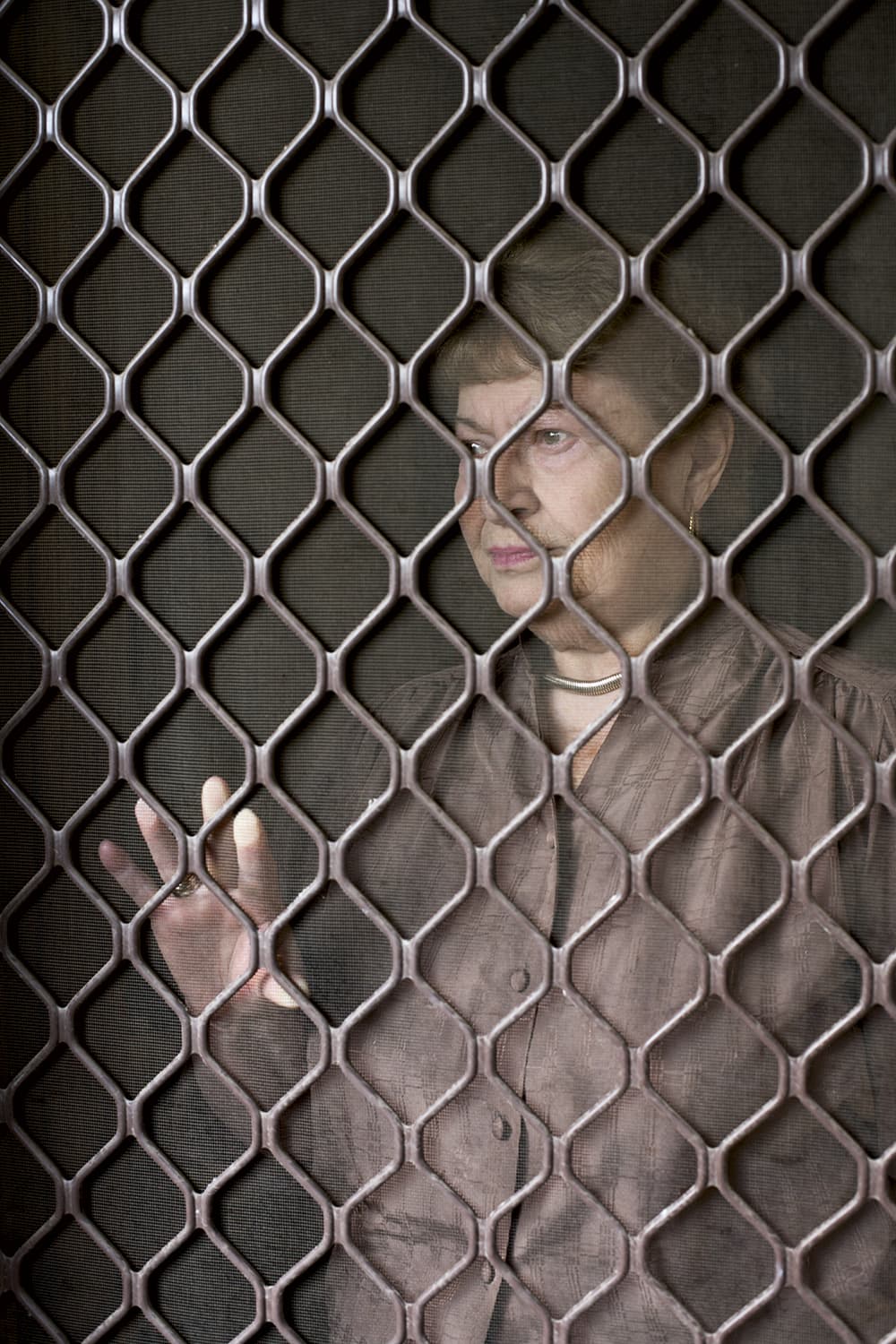

Bronia Rosenbaum. ‘There is no philosophy to describe the sadness of a lone tree with dead roots. Even if nestled in faraway woods, all one can hear is memories and tales of bygone years, and prayers promised for my soul, when I am gone.’

Today, 51-year-old Harry is a prominent, award-winning portrait photographer with a long list of famous sitters that includes Tony Blair, David Beckham, JK Rowling, Baroness Thatcher and Paul McCartney. As regular AP readers will know, he tells the story behind these shoots in our regular When Harry Met feature. More than 100 of his portraits are in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection.

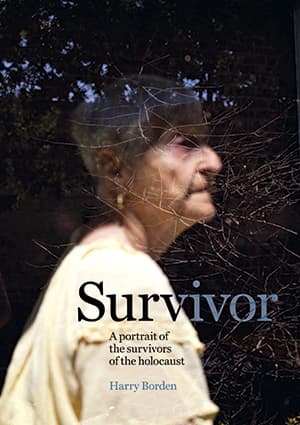

In between these assignments, Harry also works on his own long-term personal projects. This month, a project inspired by his cultural background reaches completion with the publication of his book Survivor: A Portrait of the Survivors of the Holocaust.

It’s a collection of 100 sensitive and dignified portraits of people whose lives have been affected by the Holocaust. They range from those who endured the horrors of concentration camps at first hand, to refugees rescued and brought to the UK as children via Kindertransport.

Barend (Yssachar) Elburg. ‘Being born in1940 in Holland and having survived with my parents, hidden by righteous gentiles, I feel it is my duty to work voluntarily for my fellow Holocaust survivors.’

Motivation

The idea for the book took root after Harry attended the photography festival at Arles, France, in 2008. He was impressed by displays of bodies of work on specific themes by photographers such as Vanessa Winship and Eugene Richards, and decided to work on his own personal project.

‘I’m proud of my body of professional work,’ he says, ‘But I realised I wanted to do something that was less about being phoned with a one-off commission and more about a personal exploration of my identity. Photographing Holocaust survivors seemed an obvious subject and one in which I had a personal interest. A lot of these survivors were coming to the end of their lives, but hitherto had been largely reluctant to be photographed or interviewed.’

Alicia Melamed Adams. ‘Love is forever.’

His project began when he was invited by the Royal Society of Surgeons to photograph some of its members. During discussions with one of the directors, he was given the names of two or three Holocaust survivors who were society members. After photographing them, he gave a talk about his work at the London Jewish Cultural Centre and announced his plans to the audience. In exchange for being part of the project, Harry said that anyone who was photographed would be given a print. Several more people came forward.

At this point, Harry started a website to promote awareness of the project. After doing an interview about it for the Australian Jewish News, more survivors were located and photographed, this time in Melbourne’s sizeable Jewish community.

Maria Lewitt. ‘I am grateful to Australia and its unique people for letting us into this country, giving us a chance to lick our wounds, and then to carry on with a normal life.’

The article also aroused the interest of Australian writer Miriam Hechtman, who contacted Harry and said she would like to get involved. She subsequently helped arrange an interview with The Jerusalem Post and then later the New York Times and accompanied Harry on the ensuing trips to Israel and New York.

Shooting the portraits

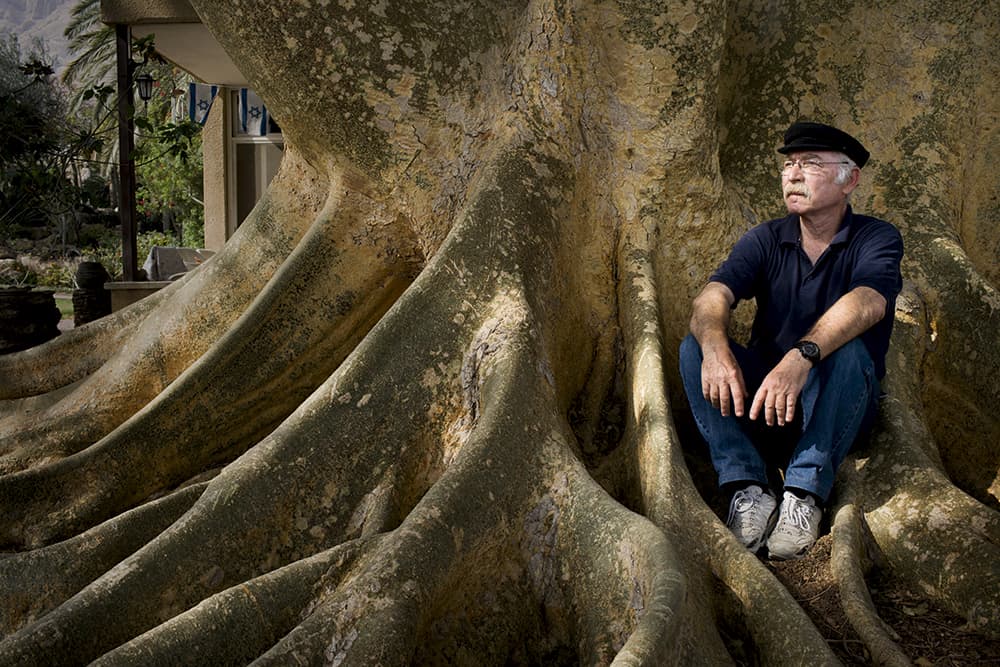

Harry took a relaxed, low-key approach to photographing the Holocaust survivors. ‘My usual modus operandi was to start off by showing sitters my work, so they could get an idea of what I wanted to achieve,’ he says. ‘I emphasised that they didn’t have to be an animated or a hyper-real version of themselves. It was simply a record of the relationship I had with the person.

‘When deciding on a specific location, I tended to look for a space within their living environment – their house, garden or nearby park, for instance – that had some interesting light and worked geometrically in the frame. Then I put them into that space. I just had a chat with them and took photographs in a very reactive way. I shot them all using available light.’

Moshe Shamir. ‘As a Holocaust survivor never to forget! Never again!’

Harry didn’t have an assistant, lights or hair and make-up artists, as he would with celebrity portraits, and he didn’t spend a lot of time taking his sitters to different locations. ‘These people weren’t promoting anything, they were just giving me their time to help me in the project out of the kindness of their hearts,’ he continues. ‘I didn’t want to put people through the wringer like I might if it was

someone like Robbie Williams and I was trying to get variety.’

To further personalise the pictures, Harry gave each person a blank sheet of paper on which they could write something about themselves. The things they wrote included specific memories, such as: ‘They took my mother and pushed me back with the butt of a gun – I knew I would never see her again.’ They also included general reflections on the survivors’ lives; one wrote, ‘I am glad to be an optimist because that’s what kept me alive.’ These handwritten notes are now shown alongside their portraits in the finished book.

Arno Roland. ‘I left Berlin in1939 with a Kindertransport to Holland, where I survived in hiding and finally came to New York/New Jersey, but without my younger brother Ulli who perished in Auschwitz. I wish to thank Miriam and Harry for their work to show some of the faces of those who outlived the Nazi nightmare.’

‘I could have made things easier for myself by just setting up a backdrop in the London Jewish Cultural Centre and banging off the portraits in one go,’ says Harry. ‘I made it difficult by doing all the pictures individually in the subjects’ own environment.

‘Each photo involved me making a trip and sometimes getting lost and knocking on the wrong door, but I wanted each picture to be a genuine moment and an intimate representation of what it was like to meet that person.’

Harry says the experience of meeting people whose lives were significantly changed by the Holocaust was sometimes funny and sometimes harrowing and profoundly sad. Some of these people had their whole family killed by the Nazis and were still scarred by the experience more than 70 years later. Others would conclude that they had defeated Hitler, because they had survived and now had many grandchildren.

Leon Rosenzweig. ‘The best time of my life is when I am with my family.’

‘It was a real emotional rollercoaster,’ Harry continues. ‘It certainly gave a completely different perspective on my own problems and really made me count my blessings.’

Getting published

Harry shot the last of the portraits in 2010. He didn’t have a clear idea about what he was going to do next, but hoped to make a book or exhibition. In between his professional work, he gradually edited and retouched the images, until in 2014 he made and designed a dummy book, which he entered into the European Publishers’ Award for Photography.

‘The book was shortlisted for the award, which was fantastic and gave me a lot of confidence,’ he says. ‘I now knew I was definitely on to something.’ He made five copies, which he then used in the process of getting the book published.

Harry was aware that getting a well-known author on board to write the book’s introduction would help attract attention. Therefore, when he shot a portrait of novelist Howard Jacobson for The Sunday Times, he took the opportunity to discuss the project and later sent him one of the dummy copies. Eventually, Jacobson wrote back to say he thought the pictures were ‘noble’ and said he was happy to write the foreword.

Lina Varon. ‘After surviving the war and the consequences of the war, every day has been and is a bonus for me.’

The process of finding a publisher for the book, however, wasn’t so straightforward. Through his professional connections, Harry approached two publishers. Although they loved the idea, they didn’t go ahead with publication.

‘Eventually, when I was photographing restaurateur Andrew Wong, I met the press officer for Octopus Publishing Group that was publishing a book of his recipes. She was really enthusiastic about my idea and the next day I had an email from Octopus’s editorial director. I sent him a dummy copy and he was very positive about it. The company subsequently made me an offer and I went with it.’

However, there was still one crucial aspect of the book that Harry hadn’t tackled. ‘During the eight years I was working on the project, I had the realisation that I needed biographies of all the sitters and hadn’t collected them at the time,’ he says. Octopus said this information would be needed, so Harry and Miriam Hechtman, often with the help of sitters and their families, combined to research and write the detailed biographies that now form the final part of the book.

Mayer Braitberg. ‘I have nothing to say.’

Survivor: A Portrait of the Survivors of the Holocaust is available now. After several years’ work in planning, shooting and designing it, Harry says he feels ‘an incredible sense of satisfaction’ to see the final product.

‘It’s nice to bring something substantial to fruition and very rewarding on a personal level,’ he says. ‘It’s very different doing something you feel compelled to do, and derive some intrinsic pleasure from, rather than having to second guess what a picture editor wants. It’s feels nice to say, this book is for my children, it’s mine.’

Harry Borden tells the story behind one of his ‘Survivor’ portraits

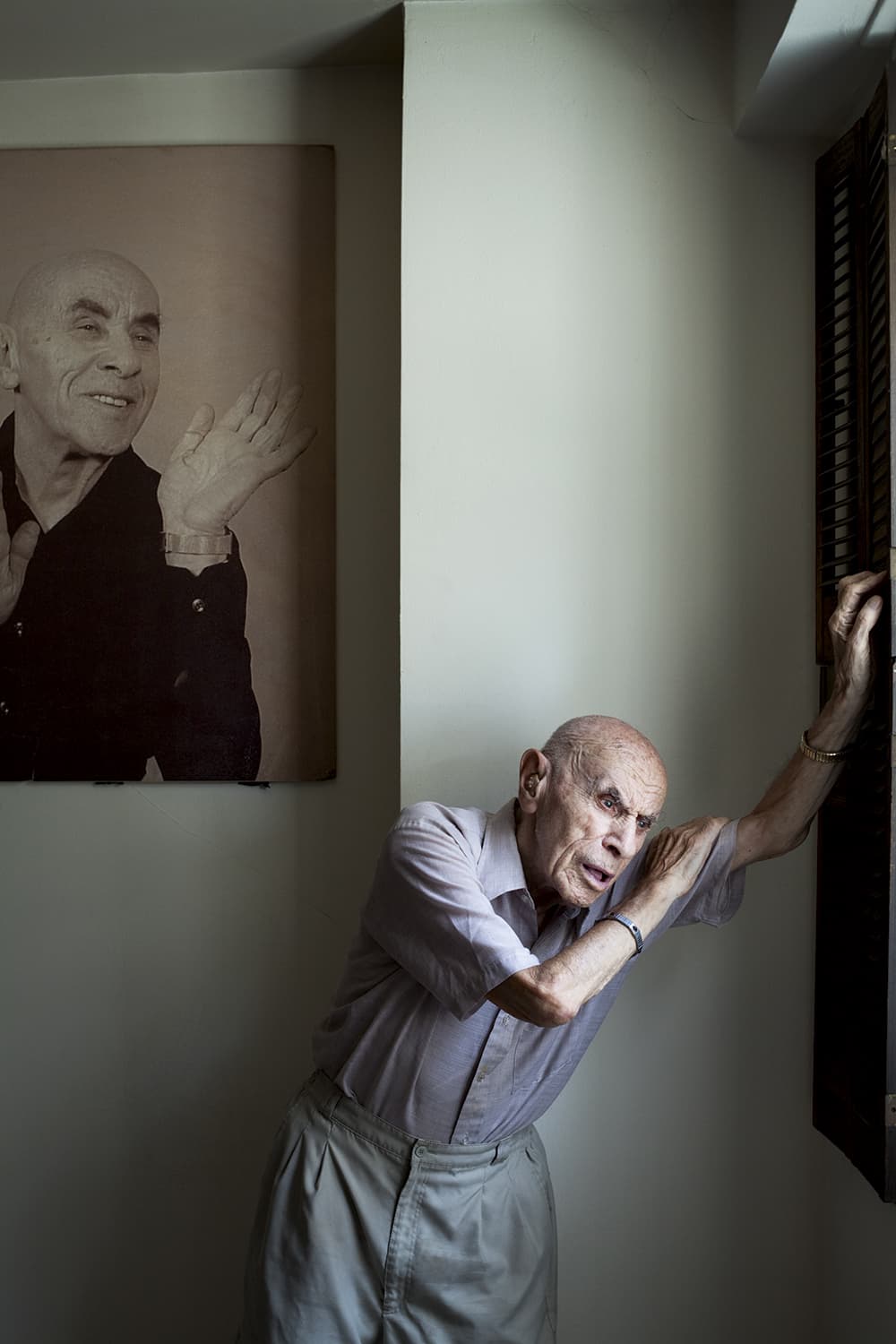

Felix Fibich. ‘In my dancing I was trying to express a full range of human emotions, from the joy of life to deep sorrow of pain and suffering of tragic life.’

‘Felix Fibich was a highly regarded dancer and choreographer. He was born in Poland in 1917, and, when the Nazis invaded, he and his family were forced to live in the Warsaw ghetto. He managed to escape, but the rest of his family was killed. He emigrated to the United States in 1950, where I photographed him over 60 years later.

‘I went to his flat in New York, where he had a carer who was obviously really fond of him. Before I started photographing him, he asked if he could express himself through dance. He went through various different moves and when he got into this particular position, I said, “Hold that a second.” ‘He was lit with daylight coming through the window. I just angled the camera so I could include the photograph of him as a younger man. I thought it was really poignant. His expression here is extraordinary, full of emotion, and it makes a powerful image.’

Survivor: A Portrait of the Survivors of the Holocaust by Harry Borden, with an introduction by Howard Jacobson, was published by Cassell on Holocaust Memorial Day, 27 January 2017.