Steve Schapiro picked up his first camera when he was nine years old. It was a 127 Kodak, and he was at summer camp. However, what influenced his career most was Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Decisive Moment. He explains, ‘I would go out and try to photograph that way – capturing the exact moment that was the height of action or emotion.’

Ralph Abernathy (rear) and Dr Martin Luther King (centre) lead the way on the road to Montgomery, Alabama, 1965

From these beginnings, Steve went on to study with the legendary US photojournalist W Eugene Smith. He recalls, ‘I stayed with Eugene Smith in 1961 and he really taught you how to make prints in terms of getting intense blacks and intense whites. Sometimes he used up to 250 sheets of paper to make one master print.’

Printing wasn’t the only thing he mastered from working with Eugene Smith. ‘I also learned a feeling for humanity from him, as well as tricks of the trade – for example, a picture works best if there are two points of interest in it. So it won’t be just a portrait of someone – there will be something else that reveals more about them, and your eye will go back and forth between the two. It becomes a more satisfying experience and you stay with the photograph longer.’

Unsurprisingly, given his tutelage under a photographer such as Eugene Smith, Steve developed an ongoing interest in journalistic photography. He reveals, ‘As I was growing up, the most important magazine you could be a photographer for was Life. I did my own projects – I went to Arkansas on my own and did a story on migrant workers there.’ That story was picked up and published, without a fee, by a small Catholic magazine called Jubilee and subsequently The New York Times Magazine.

Steve admits, ‘I would just keep going to Life. I did a story on narcotics addiction in East Harlem and took it to them. Finally, they gave me an assignment, and I started working regularly for them.’

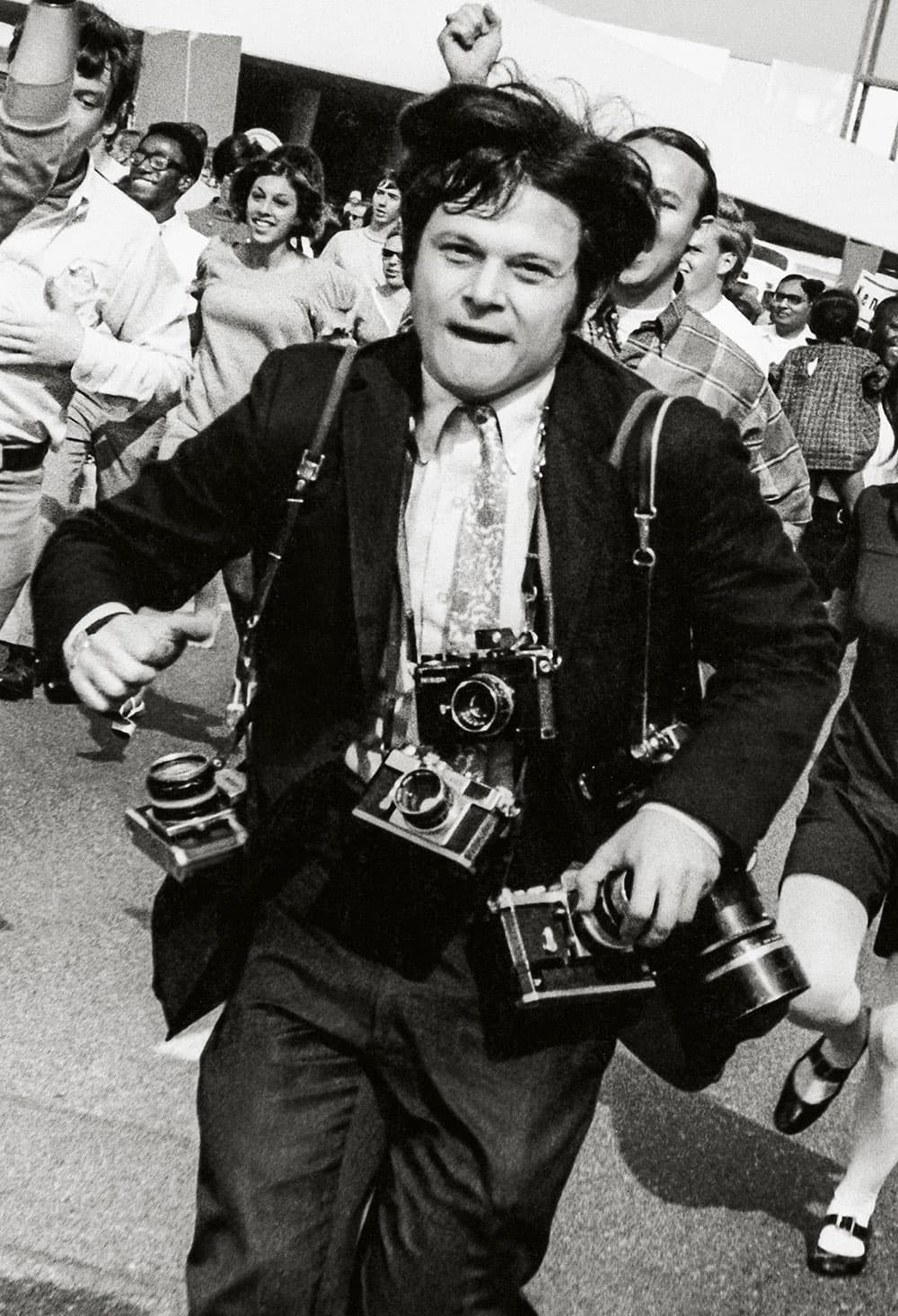

Steve Schapiro pictured while travelling with Robert Kennedy in 1966

The civil rights movement

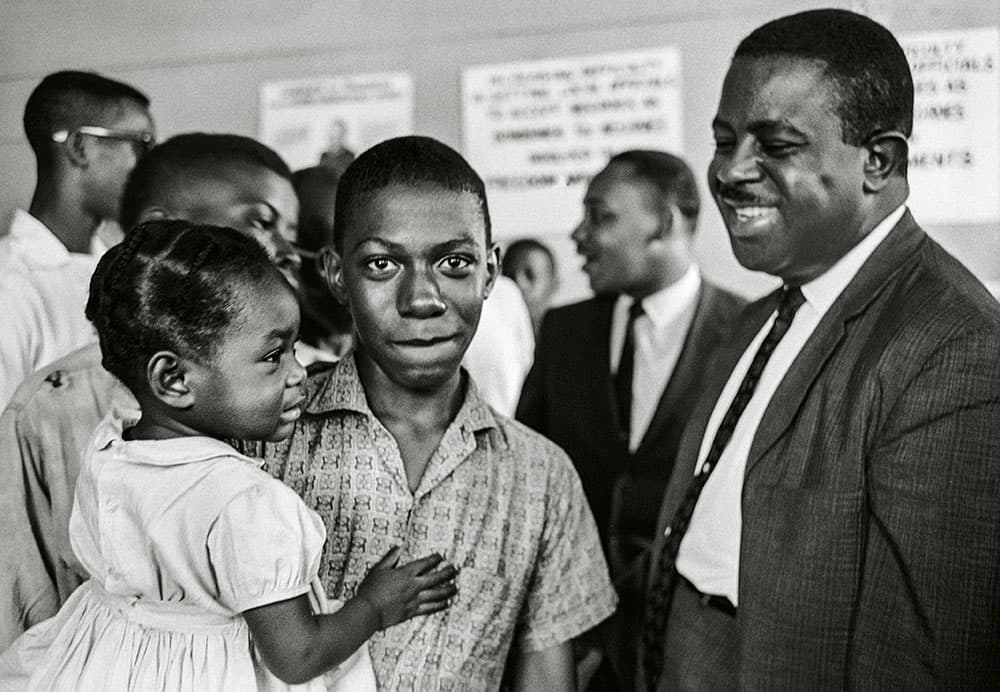

Steve’s rise to prominence as a photojournalist came through his coverage of the US civil rights movement. It started with a 1962 essay by James Baldwin, which appeared in The New Yorker and went on to become the book The Fire Next Time.

‘I read the essay and I was taken by it and taken by Baldwin,’ Steve recalls. ‘I asked Life if I could do an essay on him, which they and he agreed to. The next month, I travelled with him from Harlem to Durham, North Carolina, then on to Mississippi and New Orleans.

In the course of it, I met a lot of civil rights leaders and also became much more involved in photographing civil rights.’ Between 1963 and 1968, he continued to photograph the movement, including riots in Brooklyn, the march on Washington and, in particular, the Selma to Montgomery marches. He also frequently photographed the figurehead of the civil rights movement, Dr Martin Luther King.

‘When Dr King was shot, I was in New York, and Life had me fly immediately to Memphis,’ Steve explains. ‘When I got there, I found out the shots had been fired from a rooming house, so I went there – and there was really no security whatsoever. The shots were fired from a second-floor bathroom, where the assailant stood in the bathtub and levelled his gun on the windowsill. I saw a dirty handprint on the wall that could only have been made by someone standing in the bathtub. I photographed it and Life used it over a full page the following week.’

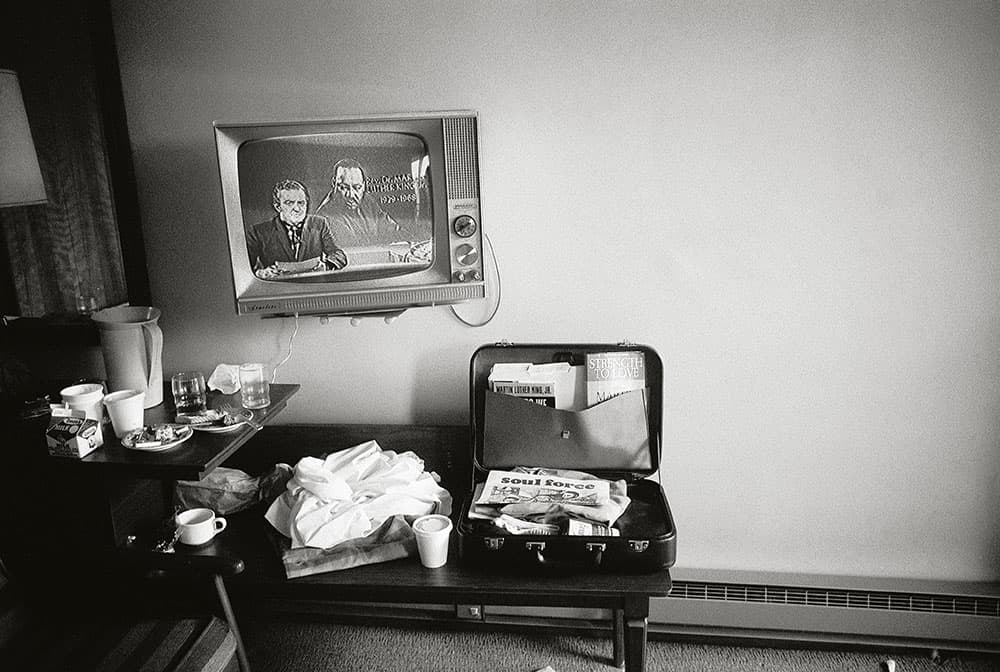

After this, Steve went to the room at the Lorraine Motel where King had been staying. ‘I saw his attaché case,’ he says. ‘Inside were his books and hairspray, and a magazine called Soul Force. There were worn shirts and old Styrofoam cups lying around. Then his image came on the television behind an announcer, and I photographed this all together. It became symbolic to me, in the sense that the physical man was gone forever, his material things remained, and yet he still hovered above us.’

Dr Martin Luther King’s room in the Lorraine Motel, Memphis, after he was shot

The haunting shot of Dr King’s empty motel room and more than 100 other images by Steve Schapiro feature in the revised edition of The Fire Next Time. For the book, Steve went through his contact sheets and uncovered some previously unpublished photographs. ‘I found four or five pictures that are particularly good and which had somehow escaped everyone’s attention. Even the picture of Martin Luther King’s motel room had never been clipped [on the contact sheet] by Life to be printed.’

Of Dr King, he notes, ‘In a lot of pictures I see him looking into the crowd – I mean, he had so many death threats and here he was, this incredible leader who really inspired and was important to so many people… yet I find his eyes searching the crowd, and I can only think that all these death threats were in the back of his mind. There was just something in his eyes that was continuous in a lot of the pictures.’

With regards to his best image from this time, Steve says, ‘The picture that probably is the most successful is of Dr King with the American flag right behind him. It’s symbolic. When you photograph someone, if there’s another element, it makes it a better picture. If there’s something that confirms who that person is in some way, it becomes interesting. As a photographer, you want as much as possible to tell who that person is.’

Steve admits that he never actually spoke to Dr King. ‘Although I did many, many photographs of him, I don’t think I had a conversation with him and, really, I only photographed him in public situations. Usually I work as a “fly on the wall”. I try to be very quiet, so I don’t interfere with who they are. If we’re having a conversation, they’re very aware of me and half the pictures will be of them with their mouth open… it becomes much more important for me to be at a distance.’

Schapiro barely noticed Dr Martin Luther King in the background when capturing this image of Reverend Ralph Abernathy, Dr King’s best friend and advisor, in Mississipi, 1963

Three-finger cameras

In the 1960s, Steve predominantly shot with Nikon S, S2 and S3 range finder cameras. ‘They were “three-finger cameras”, which is to say that with my right hand I could focus, take my picture and then advance the film, and with my other hand I could bounce strobe. Bounced strobe allowed you to do a picture that kept the whole feeling of the scene; you were aware of what was being photographed but you weren’t aware of a photographer taking the picture. I just got in the tradition of that [working one-handed] and probably have used every kind of Nikon camera as they developed into single lens reflexes. Right now, I use a D800E.’

He often carried five or six cameras at one time loaded with either Kodachrome or Ektachrome 64 colour films or his ‘go-to’ Tri-X black & white film. Each camera would have a different lens attached, including a 24mm, a 35mm, a 105mm as ‘an ideal portrait lens’ on two of the cameras and then a 180mm long lens on another.

Steve explains, ‘When you’re working at a documentary event, there’s really no time to change lenses. If you’re working in a situation that’s a very wideangle scene, and there’s something happening in it, you don’t have time to change lens when you suddenly see that there’s a close-up moment or when you want to get a very tight shot of someone. So you really have to have that extra camera.’

A court order allowed only 300 people to march to Montgomery. President Lyndon B Johnson provided security for the five-day march in 1965, which included 2,000 army troops and 1,000 military police

He adds, ‘At the end of every day, your film would go on American Airlines baggage to Life. They would get it in the morning, and they would process the film and edit it immediately. Because you were travelling, you really never saw your contact sheets before they had made all their choices for what would go in the magazine.’

When asked if he found it difficult to detach himself emotionally from certain situations, Steve replies, ‘If you’re a journalist, you feel you really have to concentrate. It’s funny, but very often if I’m on the street and there’s someone I want to photograph, I become very shy. But at the same time, if I’m in an event, like the Selma march, I have no apprehension about photographing everything and trying very hard to find good pictures out of it.’

He goes on to recall, ‘You never really realised the signifiance of what you were photographing. You might shoot six or seven rolls of film at an event such as the Selma march, and you were never sure what everyone would then decide was an important photograph. You didn’t think what you were doing was part of history… you thought you were simply photographing a news event. I didn’t realise when I first photographed Dr King that he was one of the most important people that would ever come out of this movement and period of history.’

A standoff between protestors and Alabama state troopers before the third Selma march

Steve Schapiro’s work has been on the covers of major magazines such as Life, Vanity Fair, Sports Illustrated and Time. Visit www.steveschapiro.com.

The Fire Next Time was originally published in 1963 but is now available in a revised edition published by Taschen (ISBN 978-3-8365-5103-8) in a limited edition of 1,963 copies, with an RRP of £175.