© Norman Parkinson

More Taste Than Money, British Vogue, February 1950

Vintage Silver Gelatin Print

12 ¼x11¾in/32x30cm

Norman Parkinson, born Ronald Parkinson, was one of the most influential fashion photographers of the 20th century. His work featured heavily in Vogue and other fashion magazines from the 1940s to the 1990s.

He is said to have been instrumental in breaking beyond the stiff formality of previous fashion photography and creating a more inventive, casual elegance to his shots.

The upcoming Elegance in Vogue exhibition will showcase a selection of images from his extensive archive. The exhibition coincides with the National Portrait Gallery’s Vogue 100: A Century in Style, where a number of Parkinson’s photographs will also be shown. We caught up with Elizabeth Smith, head of the Norman Parkinson Archive, to find out more about the images on show, and what made Parkinson’s work unique.

Can you tell us a little about Norman Parkinson’s career?

At the age of 16 Parkinson became an apprentice working for Richard Speaight, an established photographer in London’s Bond Street. Parkinson learned everything about the technical aspects of photography while working there.

Parkinson was exceptionally charming and very quickly became an in-demand portrait photographer specialising in perfectly lit photographs of young debutantes. His career moved quickly on from there.

He began photographing for the Bystander, Harper’s Bazaar and eventually was hired by Vogue where he was their principal photographer for many years.

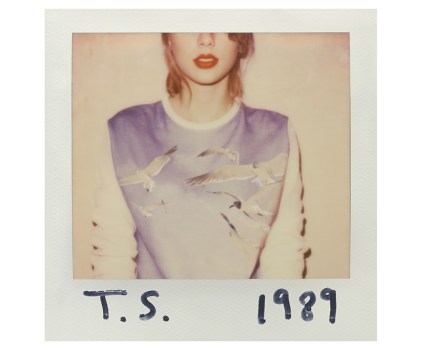

© Norman Parkingson

White Weddings (Twiggy), British Vogue, February 1967

Vintage Silver Gelatin Print

11x17in/28x43cm

What was Parkinson’s ethos and approach as a photographer?

Parkinson was incredibly hard working and expected a lot from his models. Although he was a perfectionist, he was polite and considered a gentleman.

He always claimed that he was a craftsman, not an artist, and that his pictures happened more or less by chance. However, we know from looking through his contact sheets and other ephemera here at the Archive that really the opposite was true. His lighting, his props, his overall technical expertise are obvious.

Parkinson is lauded as being one of the 20th century’s foremost fashion photographers. Why is his work considered important?

He was the first British fashion photographer to take models outdoors and have them move about.

From his earliest images – ‘Jump’, ‘Golf, Le Touquet’, or ‘Speedboat Dubrovnik’ – his models were relaxed and having fun. Yet still the fashion is obvious and carefully depicted in all its detail. He was adamant about this.

How did he influence fashion photography?

Many photographers have mentioned Parkinson as an influence, including Mario Testino, Rankin and others. They have looked to Parkinson’s expert use of light, particularly outdoors where his models glow.

What is perhaps more intriguing is that Parkinson also had an impact on fashion designers. We have done an exhibition of Parkinson’s work curated by [fashion designer] Philip Treacy and another by Roland Mouret.

© Norman Parkingson

Fashion Pure and Simple, British Vogue, February 1968

Vintage Silver Gelatin Print

20x16in/51x40cm

Parkinson’s career spanned over five decades. What changes took place in Parkinson’s work this time?

The amazing fact about Parkinson was not only the longevity of his career, but also that he managed to stay at the forefront of the changing styles in fashion and more specifically fashion photography.

He was responsible for many of the changes that took place. While his early work was primarily posed studio portraiture, he eventually began moving outdoors where his work became more spontaneous, lighthearted and fun.

How did fashion photography as a whole change during this time?

Like everything else, fashion photography was affected by the small and large, the economy, people’s standard of living, changes in social mores and obviously technological developments in cameras and lenses.

For Parkinson, once the world became more accessible, specifically when air travel became a possibility, everything opened up for him. This is when his career literally took off. Although he took many images in the UK, in the 1950s he also travelled to the US, Africa, India and the Caribbean and went further afield whenever the opportunity arose.

I think his sense of adventure was heightened by these trips and he becomes even more daring with his pictures as the 1960s arrives.

From such a wealth of material in the archive, how were the final images for this exhibition chosen?

The exhibition was selected by the Norman Parkinson Archive, with the assistance of our former Archive coordinator Jessica Gordon.

We felt it would be interesting to include some of Parkinson’s more quirky images, those that incorporated not only odd perspective andunusual lighting angles but also commonplace subjects Parkinson included such as children and dogs. Yet still the elegance of the models and the accessories shines through.

Can you talk through a couple of specific important images in the exhibition?

This exhibition really does reflect Parkinson’s adaptability. We have wonderful examples of some of his best work throughout the decades.

Our current favourite at the Archive is Parkinson’s photograph of Jean Patchett wearing Balanciaga [‘Paris Drama’, Vogue, 1950]. This is our latest limited edition and we are delighted to launch it with Eleven Fine Arts; it is particularly striking as the transparency has been meticulously reworked to its original stunning colour.

© Norman Parkingson

‘Paris Drama’, British Vogue, May 1950

Digital C-type Print on Fuji Crystal Archive paper

20x16in/51x40cm

Limited Edition of 21

Another image we have many requests for currently is ‘Jerry Hall, Jamaica’, 1975. This image with Jerry Hall talking on the telephone in a bathing cap perfectly encapsulates Parkinson’s ability to turn a very contemporary, almost sassy image into a modern classic.

‘Norman Parkinson: Elegance in Vogue’ is running concurrently with the National Portrait Gallery’s ‘Vogue 100: A Century in Style’. What does this exhibition add to the story told in the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition?

Elegance in Vogue includes a combination of iconic Parkinson works as well lesser-known images.

We think this shows Parkinson’s versatility, while also hinting at the huge number of unknown images available at the Archive.

Parkinson’s story is unique; unlike many other 20th century fashion photographers, Parkinson managed to get back all of his negatives. We have approximately 850,000 negatives and over 3,000 original photographs in our collection spanning Parkinson’s incredible career, from 1935-1990.

Are there any future plans to showcase parts of the Norman Parkinson Archive elsewhere?

We are currently putting the finishing touches to a major touring exhibition of Parkinson’s work, which should begin touring by 2018.

We have other smaller exhibitions planned this year and are also about to release Norman Parkinson with the Beatles. This is a limited-edition book, which includes mainly unseen work documenting the day in September 1963, which Parkinson spent with the Beatles.

Elegance in Vogue runs from 10 February until 24 March at Eleven Gallery in London.

The National Portrait Gallery’s Vogue 100: A Century in Style runs from 11 February until 22 May.