October 21st 2016 marked the 50 year anniversary of the Aberfan disaster. During that fateful morning, 116 children and 28 adults were killed when a colliery spoil tip collapsed onto the village, completely destroying the Pantglas Junior School.

Over in the USA, a young freelance photojournalist, I.C. Rapoport, who had been working for LIFE magazine, was moved by the footage of the disaster which was beamed around the world – one of the first times a major disaster had been televised almost as soon as it had happened.

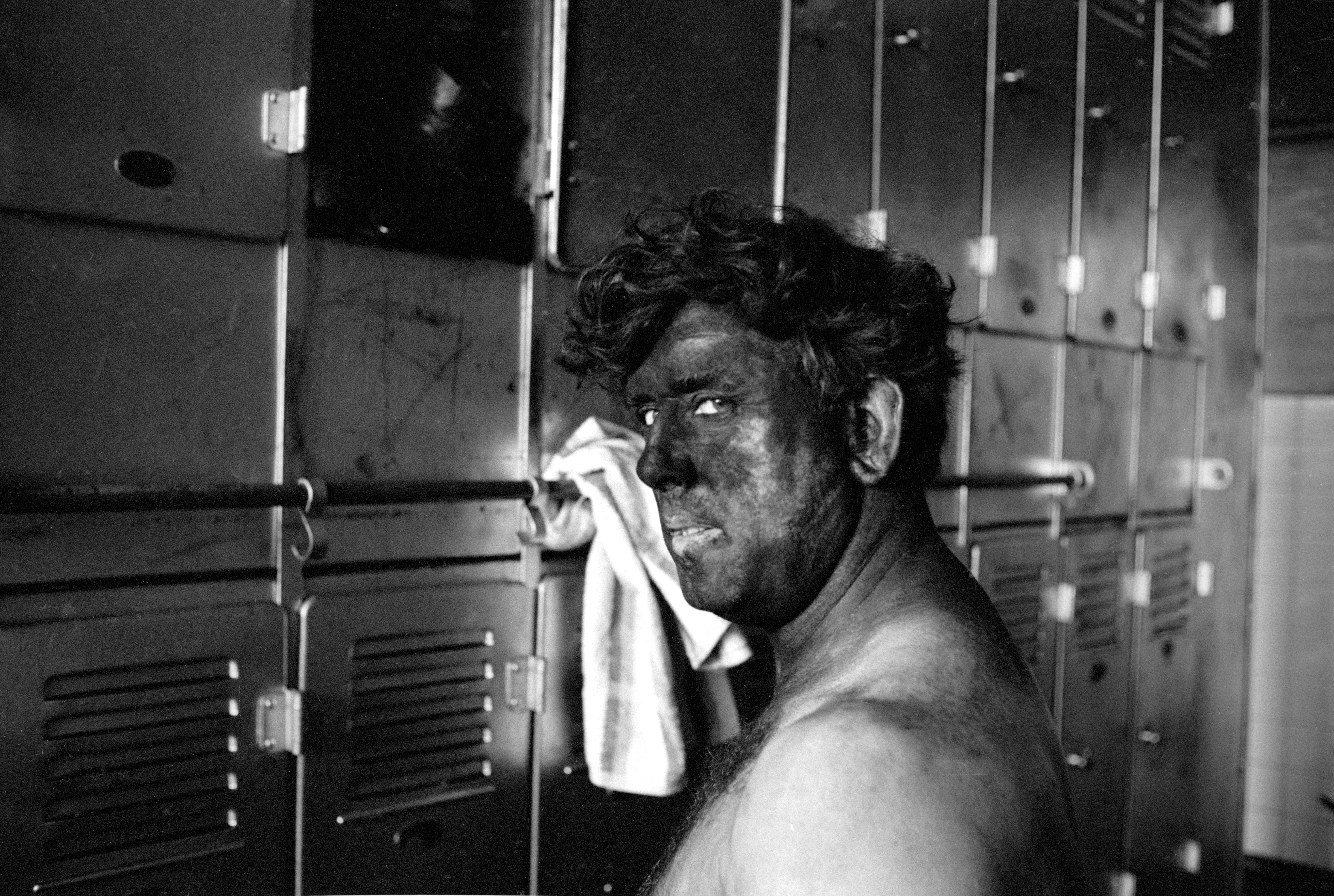

Speaking from his home in LA, Rapoport, or Chuck as he is affectionately known, describes what inspired him to travel across the globe. “I had an obsession to go to Wales. The photographer W Eugene Smith was an idol of mine, and he had shot a very well-known photo essay on Wales for LIFE magazine just after World War Two. It was a political story that he was illustrating with photographs. He went to Wales and photographed miners and sheep farmers to get a sense of the underclass of Wales and the UK. His photos were really remarkable; they were stark, black and white, crisp. Those images stayed in my mind. When I heard about this disaster in a mining villages in Wales, something told me that it had a potential for really special photos.”

Getting the assignment

Convincing his editors at the magazine to let him travel would probably be a long shot, he suspected, as he had only just started working freelance for the magazine and they were already planning to run news images in that week’s issue. Luckily, having completed a photo essay that same year which had gone down well with the editors gave him some cache. He tells us: “In the summer before the disaster, I shot a photo essay that was very well received by the editor called The Detective, about a New York City detective from the Times Square precinct, which one of their best writers wrote the text piece. When they first gave me the assignment they expected it to be a one or two day shoot. Instead, I went and lived with them, just stayed with them in their squad room. So that was a big story, it ended up being 12 or 14 pages of text and photos.

“But they continued to give me small assignments which really disappointed me. But I was young – I was 29 and I didn’t have much experience. They had a lot of photographers on their book; they had 30 staff photographers and all these freelancers that had come along before me.”

So keen was he to photograph Aberfan, Rapoport ending up speaking directly to the editor-in-chief of the magazine, going above the head of the picture editors who usually commissioned him. He bypassed the idea of covering the story from a fresh news angle, instead pitching the essay as ‘a town without children’, something the editors eventually jumped at.

“The worst kind of dirt you can imagine”

Arriving at the village around eight days after the disaster along with writer Jim Hicks, what Rapoport saw had an immediate impact. “They had cleaned up the streets,” he recalls, “but they were still covered with a half-inch of slurry, the worst kind of dirt you can imagine. My imagination of Wales based on Smith’s photos and other photos had always been a cold, wet, dirty place. When I arrived in Aberfan, my idea of Wales was reinforced – that’s exactly what it looked like. It was the end of October, it was a very cold winter that year.”

Rapoport arrived with 60 rolls of black and white film and 20 rolls of colour film, but over the next few weeks he would come to shoot over 120 rolls. He carried with him three Leica M2s – two of which he had bought upon getting the commission to cover the story, with a 28mm, a 50mm and a 90mm lens attached. He also had two Nikon F SLRs, with a 180mm lens and 400mm lens – the latter of which he says he barely used.

A town with suspicions

For a town that was coming to terms with the terrible events that had unfolded just a few days prior to Chuck’s arrival, it wasn’t easy to accept yet another journalist arriving in their midst.

“There were some people who had a very bad taste in their mouths about journalists, and so they wanted nothing to do with me. They felt the press had treated them poorly. You had a situation that was very traumatic and you had 100 journalists there and everyone is looking for a story. The journalists are under a lot of pressure to bring back a story that’s better, different or unique, and so they’re pushy. Pushy is a pretty mild word for what some of the things they did,” he explains. “I came on the heels of that – the town had cleared out of journalists by the time I arrived. But then this guy shows up with his cameras – they were very suspicious of me and cautious.

“Fortunately, being an American helped because their upset was with London, mostly, and the English. Also, I had a certain charm – I was interested in their lives and I wasn’t writing anything down.”

Although moved to take photos as soon as he arrived in the town, some subjects were naturally much harder to broach than others. “It took me a while to get to the cemetery – at least two weeks. I felt that was one place that I would really be an intruder. I was told by everybody what was going on in the cemetery – the mothers would go there two or three time a day. People said ‘You don’t want to go there, Chuck’ – but of course I did want to go there; I knew those photos would be valuable, but I was nervous about it.

“There were two entrances and somebody tipped me off to go to the top entrance. I looked in and I could see mothers and the graves, from a long distance – that’s when I used my 180mm lens. Slowly, I entered the cemetery and got closer and closer to these people. The women looked at me – some of them had a really unpleasant look on their face when they saw me up there. Others would say ‘Oh you’re the photographer from the States, the Yank’. I would talk to them. I wouldn’t take their picture but I would ask permission if I could photograph them at the grave. Some of them would say no, but most of them said to do what I wanted – they were still in shock.”

The nightmares begin

Rapoport became a regular fixture in the town, but being away from home where he had a wife and a 5-month-old baby started to take its toll and he suffered from nightmares depicting his own son being caught up in the disaster.

“I kind of separated myself from the emotion of it all. My blog series is called “Nightmares from a Disaster” because I had nightmares when I was sleeping. I would wake up in the middle of the night, because I had this baby at home. There was all this stuff going on in me emotionally: I was missing my family, missing my kid, and you know, through dreams, the longing for my kid turned into seeing my kid covered in mud and being killed. I woke up, I didn’t know where I was, in this place. I have a feeling what contributed to the nightmares was the fact that I was suppressing my feelings,” he recalls. “They were telling me horrible stories and I would just listen and nod, and try not to become emotionally involved. So it came out in my nightmares.”

Life-changing

The fate of one of Rapoport’s subjects was changed remarkably thanks to his photographs. John Collins lost his wife and two sons, along with his home and everything within it in the disaster, leaving him with not so much as a picture to prove they existed. “We went to see him, and he was weeping, he was in total shock. I had my camera on my lap and I couldn’t bring myself to pick it up and take his picture while he was going through this. Jim Hicks kept looking at me, motioning me to shoot. I was frozen. Finally, I lifted my camera and I looked and I said, ‘John, do you mind if I take a picture of you?’. He just looked at me and said ‘It’s your job, man, it’s your job’. So, he released me and I shot a whole roll of pictures.

“I never went back to Aberfan after I took those picture, so all I remember of John Collins was that he was a lost soul – I never knew what happened to him. Then, in 2010, I received an email out of the blue from a woman named Bernice Collins. She said her mom was an American woman who was so moved by my picture of John Collins in the LIFE story that she contacted him, they started a romance, got married and had a daughter – the woman who had emailed me. She said I just wanted you to know that he had a second life and he was very happy. That was so moving, I couldn’t believe it. My photograph turned his life around, him telling me to take his picture turned his life around. If he had said to me don’t take my picture, I wouldn’t have, and there would have been no photo of him in the magazine, and there would have been no American woman who would have seen him and called him. So if you put all those things together, it’s fate.”

Chuck has had contact from others in his photographs too, especially once they were exhibited in Merthyr Tydfil to commemorate the anniversary of the disaster in October 2016.

“One was a woman, who said: ‘My name is Wendy Evans. You don’t know me but I’m the little girl you photographed in the cemetery walking down the hill’. I didn’t know who she was, so she identified herself, saying ‘I’m that person’. The bride who I photographed for the first wedding since the disaster, she came to the launch of the exhibition. She came over and kissed me and hugged me and said ‘I’ll always remember you – you’re so important in my life.

Christmas delivery

Chuck stayed in the village until Christmas. “My wife came over with my son about 10 days before Christmas and I went to London to meet her. Jim Hicks, my wife and I went back to Aberfan for Christmas with a car-load of toys and we went about visiting all of the people that we had photographed and gave toys out to the kids that had survived.

“One of them is Ronnie Davies – you can look up his picture. Ronnie is the kid with the dog who goes to the wreckage of his home. I met him again in 2006, when ITV made a documentary. When I first met him and photographed him, he was a broken kid, his brother had died in the school and he was so filled with guilt. He kept saying to me, over and over again, ‘why did my brother die and not me?’ I said to him that maybe God has a plan for you and kept you alive, and that he had to honour his brother and grow up to be a good man.

“So, here I am meeting him 40 years later in his house with his wife and he asks me: ‘Do you remember what you said to me when we met?’ I said that I kind of remembered, but he remembered it verbatim. His wife was in the background and she said ‘and he’s been a good man.’ And then he went away and he left the room and he came carrying a Subbuteo game. He brought this box out, and he showed it to me, and I suddenly recalled from looking at it – it was in perfect condition. He said, ‘You gave me this game on Christmas Day when you left, and I’ve kept it ever since’. His wife said that he keeps it in a drawer, nobody’s allowed to touch it. Well, I started to cry – it was so emotional.”

The story was eventually published in LIFE Magazine in January 1967 after Rapoport had spent nearly two months living in the Welsh village. He photographed the first baby born after the disaster, as well as the first wedding. His photographs represented the people left behind, forced to move on with their lives, but it’s a hopeful piece which shows the resilience of the community. The gamble paid off; it was well received by his editors, and continues to fascinate 50 years later. Currently living in L.A., his photos were recently exhibited in Merthyr Tydfil, just a few miles away from Aberfan. The work from the LIFE essay can be viewed at Chuck’s website, along with fascinating posts about his recollections from that time. Below are some of the images that were featured in the photo essay.