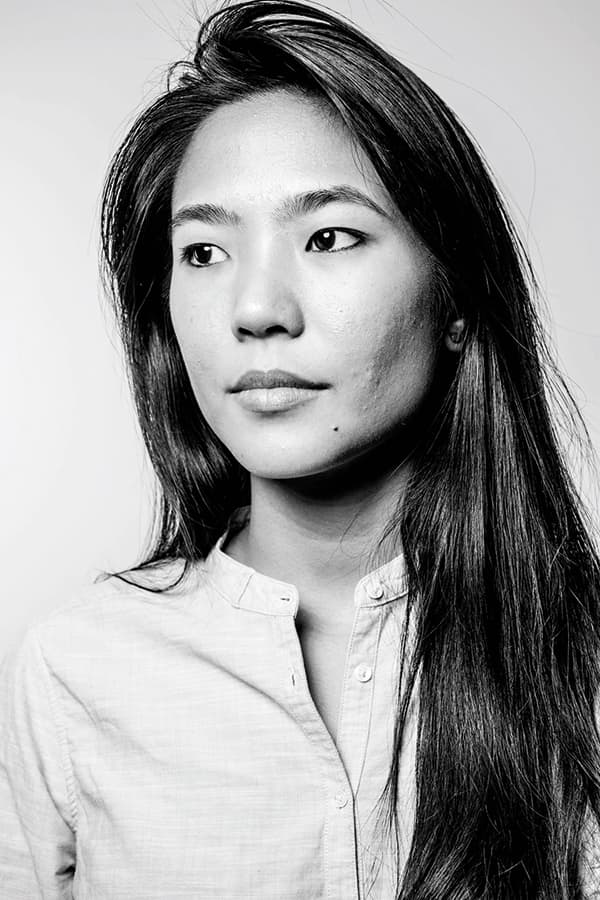

Nicole Tung, USA

Documentary and reportage photography are fast becoming our most vital assets in terms of getting to grips with a world that can seem like a spiralling vortex of conflicting and dizzying contradictions. However, thanks to a core group of photographers and journalists, we can at least get a glimpse into significant events that are key to developing an understanding of our current global and political climate. One of these photographers is the multiple-award-winning US photographer Nicole Tung, an individual whose work has become crucial in helping us form a view of areas such as Syria and Libya – both a staple in today’s news coverage.

A father comforts his crying son shortly after arriving on the shores of Lesbos, Greece, on 17 November 2015

Born in 1986, Nicole is a Hong Kong-born American citizen and is currently based in Istanbul, Turkey. She studied history and journalism in university and started freelancing for publications in New York right after graduating, covering news and features in the city for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Eventually, she was able to move into foreign reporting as a freelancer in the Middle East, which was the focus of many of her classes in school. Since then, she has been featured in exhibitions and has seen her images printed in a variety of global publications.

‘If I had to define what documentary/reportage photography is, I would say that it’s a category of photography that tells stories focusing on a wide range of issues like injustice, social conflict, war – even birth,’ says Nicole. ‘But it also covers occasions of celebrations and many others. The key aspect of the genre is why those topics are important to us. Many of the experiences that people go through might not be relatable to someone else [in another part of] the world, but the emotions and the closest portrayal of how people deal with them are quite universal. That’s where images attempt to translate and bridge a gap between people.’

For Nicole, a good documentary project should aim to be balanced and well rounded. It should have a strong narrative arc, almost as if you’re reading a book. The project has to have depth, as the photographer has invested time in the issue at hand, and that requires a real understanding of the context of the topic, too.

‘My work tends to focus on the people affected by war and conflict, because they often have the smallest voices when all is said and done,’ Nicole explains. ‘I could easily interview military commanders or soldiers to get their point of view, but I find it more telling of the story and context when I can speak to civilians who are caught up in the violence – those people who don’t have political leanings or take any particular sides but are still thrown into categories and brutalised.

‘I also think looking at people affected by war and conflict tells us so much about humanity throughout history and poses a perhaps unanswerable question: What makes neighbours turn on each other? I’m interested in the politics of identity. I’m not sure if it’s even really a unique perspective, but my role as a photojournalist is to convey images of what is going on and to let the viewers decide. Of course, there are many instances in which there are rights and wrongs, and that too is important to document.’

With so much going on in the world, it must be difficult to decide which stories to focus on, but as Nicole explains, as she matures as a person, so does the work she produces.

‘I try to choose projects that are a little bit more nuanced, and also give attention to the stories that are not necessarily well covered, or those that are under covered,’ says Nicole. ‘The stories are not always commissioned, or it may be a separate story I find while doing something on commission. I’ve also started projects that later turned into commissioned work. One example is my series on Native American war veterans that I began owing to my own interest during university. I later made it into a six-part series with a reporter, backed by Al Jazeera America. Much of how I started my career was through my own curiosity. I think it’s so important to get out there on your own and stumble upon things, or question things.

‘The kind of images I achieve during a project really depend on the situation,’ she adds. ‘When I’m taking a photograph, I think about the content of the image, its framing, and whether or not it’s reflecting the reality of what the story is. I don’t usually hope for any particular outcome. Journalism isn’t like photographing in a studio. I really try not to have preconceived notions.’

Protesters clash with police during a night of confrontation in the Mong Kok district of Hong Kong on 25 November 2014

Bertie Gregory, UK

Bertie Gregory is someone who can you make you green with envy. Aged 22, the wildlife photographer and filmmaker is already carving out an impressive CV, including working with award-winning photographer Steve Winter and presenting Nat Geo WILD’s first-ever online wildlife series. To cap it off, he has a degree in zoology.

A juvenile peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) flying in front of a Union Jack on top of the Houses of Parliament in Central London

‘My interest is primarily in wildlife; photography and filmmaking are more secondary,’ says Bertie. ‘When I was growing up, just down the road from me there were some farmers’ fields I used to walk my dog in, and I realised there was some really cool wildlife there. I started stealing my dad’s camera – he had a little DSLR – so I guess I was always exposed to cameras. I discovered that sneaking up on wildlife was good fun and taking photos of it was even better.’

A self-taught photographer and filmmaker, Bertie freely admits to learning much of his camera craft from YouTube. But his work was noticed when he was 18 years old; he was one of 20 participants chosen in 2020VISION: a UK-based project that saw 20 young photographers paired with 20 wildlife photographers.

Bertie was mentored by Alex Mustard, but adds, ‘I thought: “OK. I’ve got this mentor, Alex, who’s great, but I also have 20 other photographers who have a vested interest in this project and are going to be shooting stuff, so now I have 20 mentors.” I reached out to many of them and shot with them in the field – it was the ultimate in-the-field learning experience and it was all free.’

As a result of the 2020VISION project, Bertie was asked to become part of a wildlife roadshow that saw him and three of the pros touring the UK discussing their work. This then led to an invitation to speak at the 2013 WildPhotos event.

‘National Geographic wildlife photographer Steve Winter was giving a talk that year, so [he] was in the audience,’ says Bertie. ‘Word got out that he needed a new assistant and he was getting mobbed in every break between the talks. I thought there was no point trying to compete with that, but I’d got 15 minutes [during my talk] when he had to be listening and no one could interrupt me, so I kind of saw it as a job interview.

Raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

‘I went for broke and spent the first minute of my talk doing an impression of Steve’s American accent,’ Bertie continues. ‘The night before I’d been at the speakers’ drinks and he was buying me shots, so I basically retold the story of how surreal it was to have your photographic idol buying you shots… and I did this in his American accent. He came up to me afterwards – and luckily he had found it funny – along with Kathy Moran, Natural History Editor for National Geographic. They asked me if I wanted a job. I thought about it for about 1.5 seconds. I finished my last year at university and the day after that I got on a plane to go to South Africa to start on his leopard project (Learning to Live With Leopards).’

Bertie describes working with Steve Winter as, ‘A total rollercoaster ride. One of the things I realised was that Steve does all these amazing things and it ends up as ten pictures in one of the world’s most famous magazines. But it’s ten pictures – that’s it. So I thought, why don’t I video it and then we pitch that to National Geographic television and make a TV programme? I filmed Steve all summer, cut it into a little trailer and showed it to National Geographic television and they agreed to it. Every assignment since then has been Steve shooting stills, and I’ve been shooting video of him and what he’s shooting for National Geographic television.’

Indeed, Steve Winter says of Bertie: ‘One of the first reasons I liked Bertie was his positive attitude. It’s very difficult out in the field for months at a time and I have no time for negativity. Every problem has a solution and Bertie seemed like a guy who would fit that. He is insatiable when it comes to new ideas and ways to shoot still images and video. Our job is to find new ways to get people to look at our stories and give people a reason to care about the subjects. Bertie loves what he is doing and knows what he wants to do.’

Bertie explains: ‘After we’d finished [shooting] leopards, I pitched my first solo project for National Geographic. I spent three months on the west coast of Canada and that’s Nat Geo WILD’s first-ever online series, which is pretty exciting. In each episode I track down a different charismatic predator and the overriding aim of the series is to find the coastal wolf.’

From late June 2016 onwards, anyone can watch the 16-part series online on the Nat Geo WILD website, with a new episode being uploaded every week.

So what does Bertie think of his career so far? ‘You get lucky breaks, and meeting Steve was lucky, but I like to think you make your own luck,’ he says. ‘It’s also about recognising when you get that lucky break and jumping at it.’

A great crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus) feeds its recently hatched chicks that are sitting on its partner’s back on a misty river at sunrise

Alex Benetel, Australia

Most of us can remember the feeling of mystery that bedtime stories evoked. Everything about the words seemed real, as if we were hearing some strange truth from a faraway place, and then the dreams that would follow seemed to confirm the veracity of these tales. This is something that often gets lost in the adult years, which is a shame really, because who among us doesn’t long for those days of credulity?

‘Her Departure’, featuring fellow photographer Annaliese Bakes

Perhaps this is the reason behind the success of Australian photographer Alex Benetel’s work. Each of her portrait images can take us back to those murky worlds of dream and mystery. Each frame appears to tell a story, but the story is only hinted at. The images give the viewer’s imagination room to breathe. It would be a little obvious to refer to the images as fairytale-like. Nonetheless, there is something folkloric about them. They’re strangely familiar, yet oddly unreal.

‘I’ve always loved photography, but my passion for it [was] really sparked when I was in high school,’ says Alex. ‘In year eight, I took a visual design course that introduced me to pinhole photography and I absolutely loved it. Pinhole photography taught me about the importance of planning and not giving up on concepts (specifically when they don’t turn out). Also, working with film photography in the darkroom allowed me to develop a deeper understanding of composition and angles. The entire process from beginning to end takes time and isn’t a “one-step” process. My photography today is very similar in that regard. I have to plan, location scout, shoot, review the photographs, edit and finally share them. It’s a lot of work.’

It was a little later that Alex’s teacher encouraged her to look at Flickr and see how her ideas could be further developed by exploring the work of others who shared similar sentiments to herself.

‘I soon stumbled upon a community of talented young photographers,’ says Alex. ‘I was fascinated and decided to experiment with self-portraiture. Since then, I haven’t stopped sharing my work. Each photograph marks a moment in time in my life. My photographs today still have that incredible quality; I’m forever able to look back on each photograph and remember what was going on at that particular time.

‘Brought Back to Life’, a self-portrait

‘Flickr was so important to me in the beginning,’ she continues. ‘It really opened my eyes to the different types of photography. I had never heard of people taking pictures of themselves in public locations and not being embarrassed by it. I had never thought about taking props into a forest in order to create a fictional world. I just didn’t ever think about “creating” a photograph – I always just considered it as “taking” a photograph. Flickr introduced me to people around the world… people who shared the same passion as I did. There are friends I have today who I don’t believe I would have ever spoken to if it weren’t for Flickr. It’s sad to see some photographers I followed back in the day not posting any more. But it has honestly been amazing to watch some of my earlier inspirations over the years and seeing them grow as artists.’

Alex’s work focused primarily on self-portraiture perhaps because of the fact that, as she herself says, she was always available, easy to direct and a little too embarrassed to ask anyone else to model.

‘Self-portraiture is extremely therapeutic,’ says Alex. ‘Also, when a vision is so clear in my mind, it can sometimes be hard to explain to another person. Ultimately, it then comes down to the fact that I just feel more comfortable modelling the concept. When I started photographing other people it definitely pushed me out of my comfort zone! However, in saying that, I’ve really gone back to my roots, as I can be quite spontaneous when taking pictures of other people. Usually when I take photographs of myself, I plan the concept and take my time getting the shot. When I shoot other people, I don’t plan as much.’

‘High Altitude’, featuring Becky Chatfield, a member of the Wagana Aboriginal Dancers

These days Alex also works with digital photography, something that began when she was given a digital point-and-shoot camera for Christmas back in high school. She’s almost entirely self-taught with her digital tools and has been aided by research conversations with other photographers, as well as a great deal of experimentation to perfect her shooting and editing techniques today. So that’s now covered, but what about the future?

‘I’m at this time in my life where I’m trying to figure out what I want to do,’ says Alex. ‘I’ve recently graduated from university with a Bachelor of Education (Primary) and have been casual teaching for a couple of months now. But I’m always thinking about photography and I’m trying to work out where I want to take my passion. My short-term goal is to travel and photograph my adventures. I’m trying to not think long term just yet, because I’m happy to be flexible. For the first time in my life I don’t have a set schedule to stick to, and I’m really liking it!’