In August 1945, the war in Europe was over. Germany had formally surrendered on 8 May and the long process of rebuilding Europe’s shattered cities had begun. Yet despite the increasing intensity of the USA’s bombing of Japanese cities, including Nagasaki, the Pacific War continued.

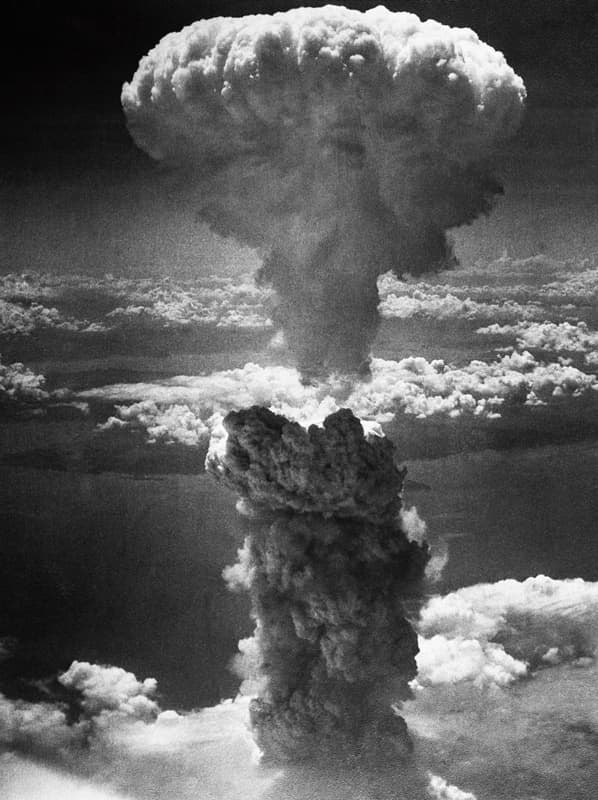

Image: The atomic bomb’s mushroom cloud soars above Nagasaki. © Bettmann/Corbis

On 26 July, the combined governments of the USA, Britain and China set down the terms of Japan’s unconditional surrender in the Potsdam Declaration. It ended with a chilling warning: ‘The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.’ Japanese Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki did not accede to the call for surrender, although doubts subsequently arose as to whether his refusal to comment was misinterpreted as disdainfully ignoring the demand.

Plans had been made for an invasion of Japan, codenamed Operation Downfall, for October 1945, but official estimates indicated that the US military was likely to suffer heavy casualties in the process. Instead, the US and Britain agreed to the use of atomic weapons, which had been developed by the joint government-funded programme known as the Manhattan Project.

The first city chosen for bombing was the industrial city of Hiroshima, which supplied armaments to the Japanese military and which was also the location of several military camps. It had a population of around 350,000.

On 6 August, the B-29 Superfortress bomber, Enola Gay, took off from the airbase on Tinian, an island in the Pacific Ocean. It was carrying a bomb – nicknamed ‘Little Boy’ – packed with 64kg of uranium, which exploded over the centre of the city. The resulting blast and firestorm killed around 70,000 people and injured a similar number, while also destroying 69% of Hiroshima’s buildings.

In a statement several hours later, President Truman announced that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan and warned that if the Japanese did not surrender, ‘they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth’.

Still there was no surrender, and on 9 August another B-29 aircraft, Bockscar, took off from Tinian with the city of Kokura as its main target. Nagasaki, an important port in southern Japan, was its secondary target. The plane was carrying a bomb nicknamed ‘Fat Man’, which contained 6.4kg of plutonium.

The Bockscar was accompanied by two other B-29s (named The Great Artiste and Big Stink), which were to observe and record the mission. Among those on board The Great Artiste was 26-year-old Lieutenant Charles Levy, from Philadelphia, who was using a 5x4in camera to record the blast.

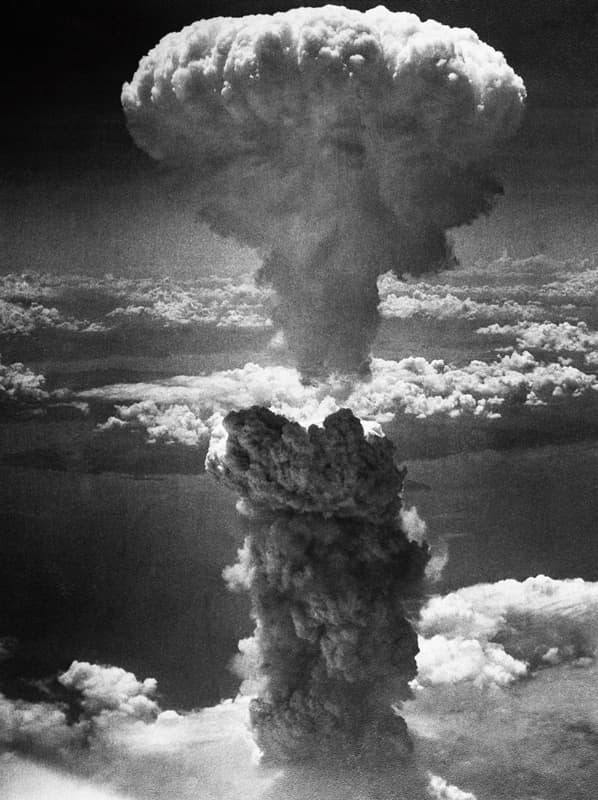

Image: The aftermath of the atomic explosion in Nagasaki, August 1945 © Underwood & Underwood/Corbis

Also on board was William L Laurence, a science journalist on The New York Times, who later described being invited by Levy to take his front-row seat in the transparent nose of the ship. ‘From that vantage point in space, 17,000 feet above the Pacific, one gets a view of hundreds of miles on all sides, horizontally and vertically,’ he wrote. This was the position from which Levy shot his photographs.

When the plane flew over Kokura, the city was obscured by heavy cloud, so a decision was made to head for Nagasaki. Shortly after 11am, the ‘Fat Man’ bomb was dropped over the city. In a 1945 interview with the Free Lance-Star newspaper, Levy recalled the moment it exploded.

‘We all grabbed our black welder goggles and slipped them on. Even though it was broad daylight, the flash could hurt your eyes. Then the flash came – sharp and brighter than double daylight itself inside our plane – and we ripped the goggles off again. We saw this big plume climbing up, up into the sky. It was purple, red, white, all colours – something like boiling coffee. It looked alive… we were all plenty scared.’

William L Laurence also gave a vivid description of the explosion. He described ‘a giant ball of fire rise as though from the bowels of the earth’ and then ‘a giant pillar of purple fire, 10,000-feet high, shooting skyward with enormous speed’. This pillar developed a mushroom-shaped head, ‘seething and boiling in a white fury of creamy foam’ until the head floated upwards to 60,000 feet and another mushroom cloud took its place.

Laurence continued: ‘As the first mushroom floated off into the blue, it changed its shape into a flower-like form, its giant petal curving downward, creamy white outside, rose-coloured inside. It still retained that shape when we last gazed at it from a distance of about 200 miles.’

Levy shot several images of the explosion at different stages, but the most powerful image captures the terrifying spectacle as the mushroom cloud climbed into the stratosphere, its billowing white top highlighted against the dark background. This was the image of the bomb that America presented to the world, while photographs of the devastated city and its tens of thousands of civilian dead were rarely seen.

Although the bomb had missed its target by almost two miles and part of the city had been shielded by surrounding hills, the blast and firestorm, which reached 3,900°C, immediately killed an estimated 40,000 people. As with the Hiroshima bomb, thousands more died subsequently from their injuries or as a result of radiation poisoning.

The debate about whether the use of atomic weapons was absolutely necessary still continues, but the immediate effect of the Nagasaki bomb (combined with the Soviet invasion of Manchukuo on the same day) was to force Emperor Hirohito to announce Japan’s surrender on 15 August. The Second World War officially ended on 2 September when the Japanese surrender was formally accepted.

Charles Levy was discharged from the US Air Force later that month, to return to Philadelphia to take up a job as a salesman. He later became a city fire inspector and died in 1997, aged 79. Today his name is mainly remembered by photographic and military historians. His iconic photograph remains a chilling symbol of the destructive power of nuclear weapons.

Nagasaki – Books and Websites

Books: The consequences of dropping an atomic bomb on Nagasaki are explored in Nagasaki: The Massacre of the Innocent and the Unknowing by Craig Collie (Portobello Books) and in Hiroshima Nagasaki by Paul Ham (Doubleday).

Websites: William L Laurence’s eyewitness account of the Nagasaki bombing can be read on www.atomicarchive.com (search for William L Laurence). Further historical background and images are available on a number of websites including www.wikipedia.com and www.atomcentral.com.

Events of 1945

- 22 January: Franklin D Roosevelt is inaugurated as US President for an unprecedented fourth term

- 27 January: Nazi death camps at Auschwitz and Birkenau are liberated by Soviet forces

- 4 February: The Yalta Conference begins, at which Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin discuss the reorganisation of Europe after the war

- 13-15 February: The Royal Air Force bombs Dresden in Germany, unleashing a firestorm that kills tens of thousands of people

- 18 March: Berlin is attacked by 1,250 US bombers

- 12 April: Franklin D Roosevelt dies suddenly from a cerebral haemorrhage and is replaced by Harry S Truman

- 30 April: As the Red Army approaches Berlin, Adolf Hitler and his wife Eva Braun commit suicide

- 2 May: Berlin falls into Soviet hands and soldiers hoist the Red Flag over the Reichstag

- 8 May: The end of the war in Europe is celebrated in V-E Day

- 1 July: American, British and French troops move into Berlin

- 16 July: The Potsdam Conference begins, at which the Allies divide up Germany and call for the unconditional surrender of Japan

- 6 August: The United States drops an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, a further atomic bomb is dropped on Nagasaki

- 2 September: The Second World War officially ends as the Japanese surrender is accepted by Supreme Allied Commander General Douglas MacArthur